The 411

A deep dive on apparel screen printing inks.

Published

2 years agoon

I’M OFTEN ASKED, “What’s the best apparel screen printing ink?” My mind immediately begins to race through all the different kinds of ink. That’s the beauty of screen printing. I can print an enormous range of substrates using the same printing technology. In fact, screen printing is the most diverse printing process for end applications. I can print plastic, metal, fabric, wood, leather… the list goes on and on. For each of these substrates, there can be a wide range of inks depending on the desired print result. Apparel is no different.

Apparel Screen

Ink Classifications

In screen printing, the final product determines the available substrate options. The specific substrate that’s chosen will then determine the available ink system(s). But it doesn’t stop there. There can be several options, and chemistries, of ink for a given substrate and most will perform adequately. Let’s dive into the major classifications of apparel screen inks.

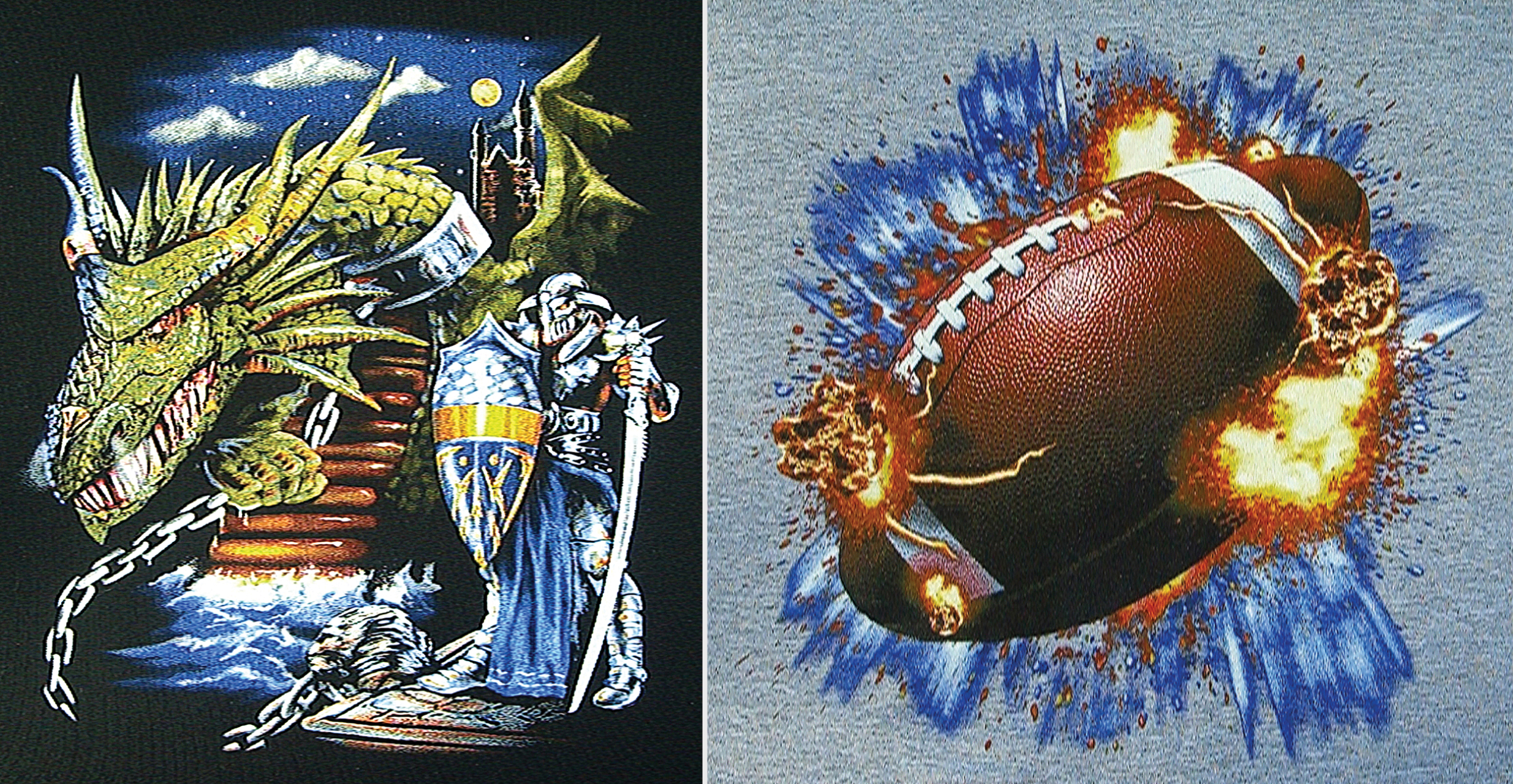

Garments printed with simulated process plastisol ink.

Plastisol

Plastisol has been the dominant ink of choice because it’s easy to use and somewhat forgiving. It doesn’t dry in the screen so you can leave the ink in the screen overnight and continue printing the next morning with no issues; it’s relatively inexpensive; and it has adequate stretch and high opacity. The ink covers the shirt color well and is more forgiving. If needed, you can cover up a mistake with another print pass. Plastisol ink is thicker than water-based ink and will sit up above the shirt a little more than water-based ink, creating more dimension to the print and a heavier hand feel. Plastisol ink is also more rigid compared to water-based ink. If you scrunch up a garment, plastisol ink will feel stiffer.

The two primary ingredients of plastisol ink are PVC resin and plasticizer. Under heat, the PVC resin absorbs the plasticizer and transforms the ink film into a solid. Their PVC- or plasticizer-based chemistry means they only dry or cure at high temperatures. In 2008, the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act led to removal of phthalates from plastisols, altering the formulation, price, and printability of the inks. Since then, major brands have demanded print providers use only PVC-free inks on their garments. Because PVC-based inks do not align with brand expectations, newer formulations are available that are PVC-free and use acrylic polymers.

Standard plastisol inks are just that. They can be used for everyday printing of simple designs and matching custom colors, and are best for 100-percent cotton apparel. When customers want polyester or cotton/poly blends, it’s best to use a low-bleed plastisol ink that cures at a lower temperature. These inks contain low-bleed ingredients to help reduce dye migration, which is common when printing polyester. Dye migration occurs with polyester dyes. When you print these colored polyester fabrics and send them through a conveyor dryer, the dyes are released. You may have seen this when printing red polyester with white ink that turns the white ink into a pink shade. Low-bleed inks are designed for use on blends. Their formulation is designed to block the dye that may be released from the polyester fibers and prevent the color from tinting the ink.

Nylon is another common fabric that causes problems for screen printers. Nylon fabrics are usually woven vs. knitted, are very slick, and often have a water-repellant coating. Most ink manufacturers offer catalyst additives, or a nylon base, that will bond with the fabric.

There are also a range of white inks available to apparel screen printers, so make sure you use the correct white ink when printing. Mixing whites are formulated specifically to be used for mixing colors. The ink manufacturers usually make them as part of a mixing system, and they’re not as opaque as whites designed to be used on their own. Athletic whites have added ingredients to give the ink extra stretch and gloss. They’re designed to be used on athletic jerseys where flexibility, abrasion resistance, and opacity are all important. Low-bleed and polyester whites are designed for polyester and blended fabrics. Athletic inks are much thicker and are designed for printing athletic jerseys. They’re very durable, but can be difficult to print due to their thick viscosity.

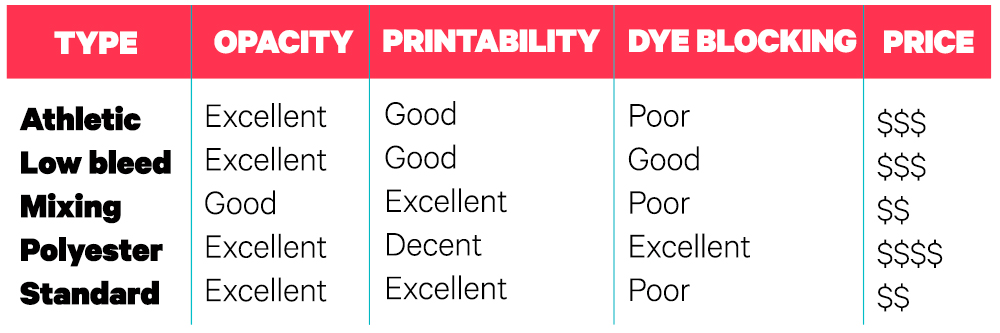

Plastisol Ink Quick Reference

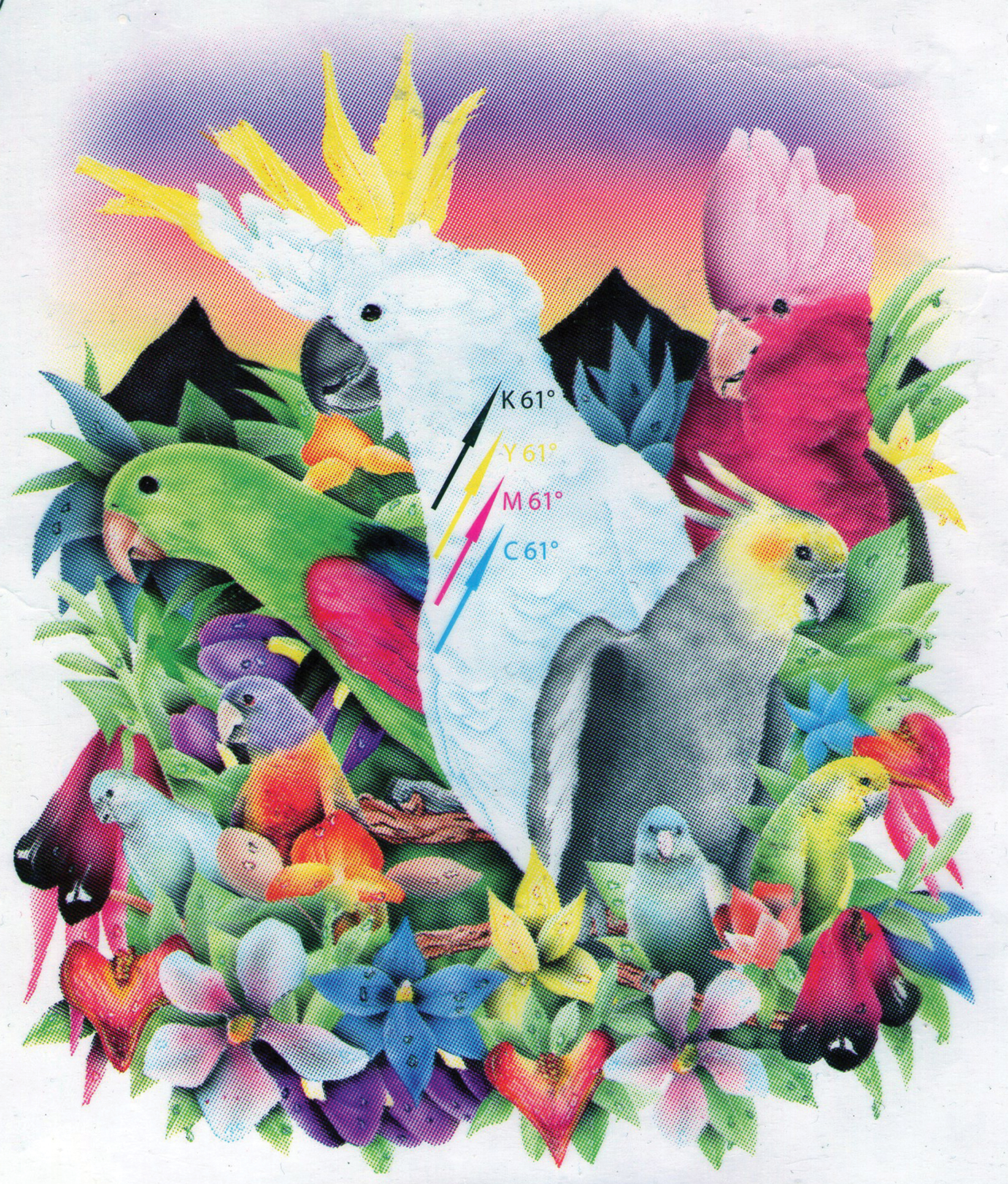

Four-color process inks are transparent inks specifically designed to print photorealistic images. I wouldn’t recommend beginners start with four-color process images, but with enough experience and consistent control of the variables of screen printing, success with four-color process is achievable. Four-color process involves four colors (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black) that are printed with halftones and, if done right, can produce a full spectrum of color. It’s great when the number of colors in the image to be printed far exceeds the capabilities of the printing press. Only four screens need to be made! However, due to the transparency of the inks, minor changes in the printing step (squeegee speed/pressure, mesh count, etc.) can cause color shifts. Documentation is key to success, especially for for re-orders, to ensure the print closely matches previous prints.

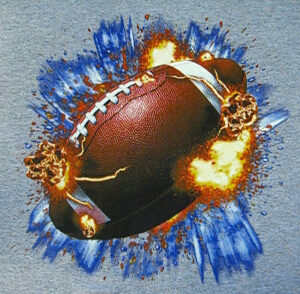

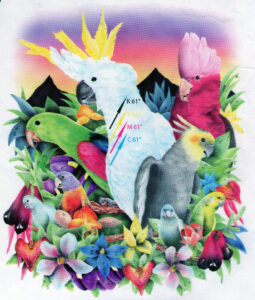

Four-color process inks are designed to to print photorealistic images and include cyan, magenta, yellow, and black.

Pros/Cons

of Plastisol

The biggest advantage of plastisol ink is the user friendliness. It can be left in the screen, or in open containers, without drying out (provided there are no additives like nylon catalyst). Most plastisol inks are ready-for-use (RFU) and can be used straight from the container. Ink that remains after a print job can be returned to the container for later use, which reduces waste.

Because plastisol is a thermoplastic, it can’t be ironed. I know… who irons a T-shirt? Still, if the ink encounters an iron (or other heat source), it can smear the ink. Plastisol ink has a heavier hand feel than water-based alternatives. The biggest disadvantage of plastisol is the ink itself and the chemicals necessary to clean it up. To emulsify the ink to remove it from the screen, some type of solvent must be used. The waste ink and the solvent must be properly disposed of to minimize potential environmental impact. Solvents are available that are sensitive to the environment, more so than traditional petroleum-based solvents. Chemical manufacturers have done a great job improving the effectiveness of their cleaning solvents and improving the environmental friendliness at the same time. There are also many types of filtration and cleaning systems available to capture inks and waste residue to reduce the number of solids discharged into the sewer system.

Plastisol

Do’s and Don’ts

Do’S

- Always stir the inks prior to use, even if they are RFU.

- When using a flash, bring the press platens up to temperature prior to starting the job for consistent print results.

- Use the correct ink based on the fabric and image to be printed.

- It’s good to do wash tests to ensure you’re achieving proper cure. While time consuming, wash tests provide a 100-percent guarantee your prints are fully cured.

Don’tS

- Overlook the importance of proper cure testing.

- Have the mentality of “any ink will work for this.”

- Overlook fabric characteristics (color, weight, fiber type). Dark fabrics heat more quickly than light/white fabrics. Adjust cure times accordingly.

Silicone inks are another appropriate PVC-free option, and they align with ecological demands of the market. Compression fabrics prone to dye migration fit very well with silicone inks because they can cure as low as 250 F. Silicone inks require a catalyst to fully cure, which gives them a relatively short shelf life and generates waste. Silicone inks are best used when printing onto polyesters and other synthetic fabrics that are prone to dye migration; silicone is a natural migration blocker so there’s no need to worry. The elasticity, washability, and dye migration resistance of silicone inks are superb, though they come with the highest price tag among all screen printing inks designed for apparel. Not only are silicone screen printing inks expensive, but the mixing systems that are available are not as robust as other ink chemistries.

A print featuring a water-based soft base with a foil application. Photo courtesy of Virus Inks.

Water-Based

Water-based inks have gotten lots of attention over the last decade. As previously mentioned, apparel brands are eager to be sustainable in their businesses and reduce environmental impact. While many screen printers are die-hard fans of plastisol, the new generation of apparel decorators have entered the industry through the water-based door. They, too, want to reduce their impact by offering an environmentally friendly product to their customers.

As the name implies, the solvent in water-based ink is water that evaporates to leave the colorants behind. The newest water-based inks are designed to mimic plastisol inks while on press and have been formulated to give the maximum open time in the screen. While they are water-based, the inks are opaque and extremely vibrant and can be used on both dark and light fabrics. High Solids Acrylic (HSA) inks are probably the most well-known water-based inks and are used on 100-percent cotton, as well as fabrics like Lycra or spandex that are popular in the apparel market. HSA inks are being specified for use by marketing agencies and brands like Nike.

Water-based inks produce very soft prints, which is one of the major advantages of using it compared to plastisol. Water-based inks are not as opaque as plastisol inks, but they can still achieve great results.

Using water-based inks requires a different mindset vs. plastisol ink. If you’re a current plastisol user and want to switch to water-based inks, one important change will be to the emulsion you’re probably using. You’ll need an emulsion that’s water-resistant so it will last during the print run. Because water-based inks contain water, the ink will quickly degrade the stencil if it isn’t water-resistant. You’ll also want to keep lids tightly sealed on ink containers so the water doesn’t evaporate. Humidity is a good friend, especially while on press. Newer automatic presses offer humidification add-on accessories that mist water in and around the printheads. Once exposed to air, the water begins to evaporate, so take the necessary preventative measures to keep the water in the ink. If you take a break, flood the screen, or wipe off the image area before you walk away. Finally, a change to the standard print stroke is needed for the best results. With plastisol inks, the screen is flooded and then the squeegee performs the impression pass; the screen sits until the next print stroke. With water-based inks, we want to reverse that, so the screen remains flooded while waiting for the next print. Most auto presses allow this to be changed with a flip of a switch.

Advertisement

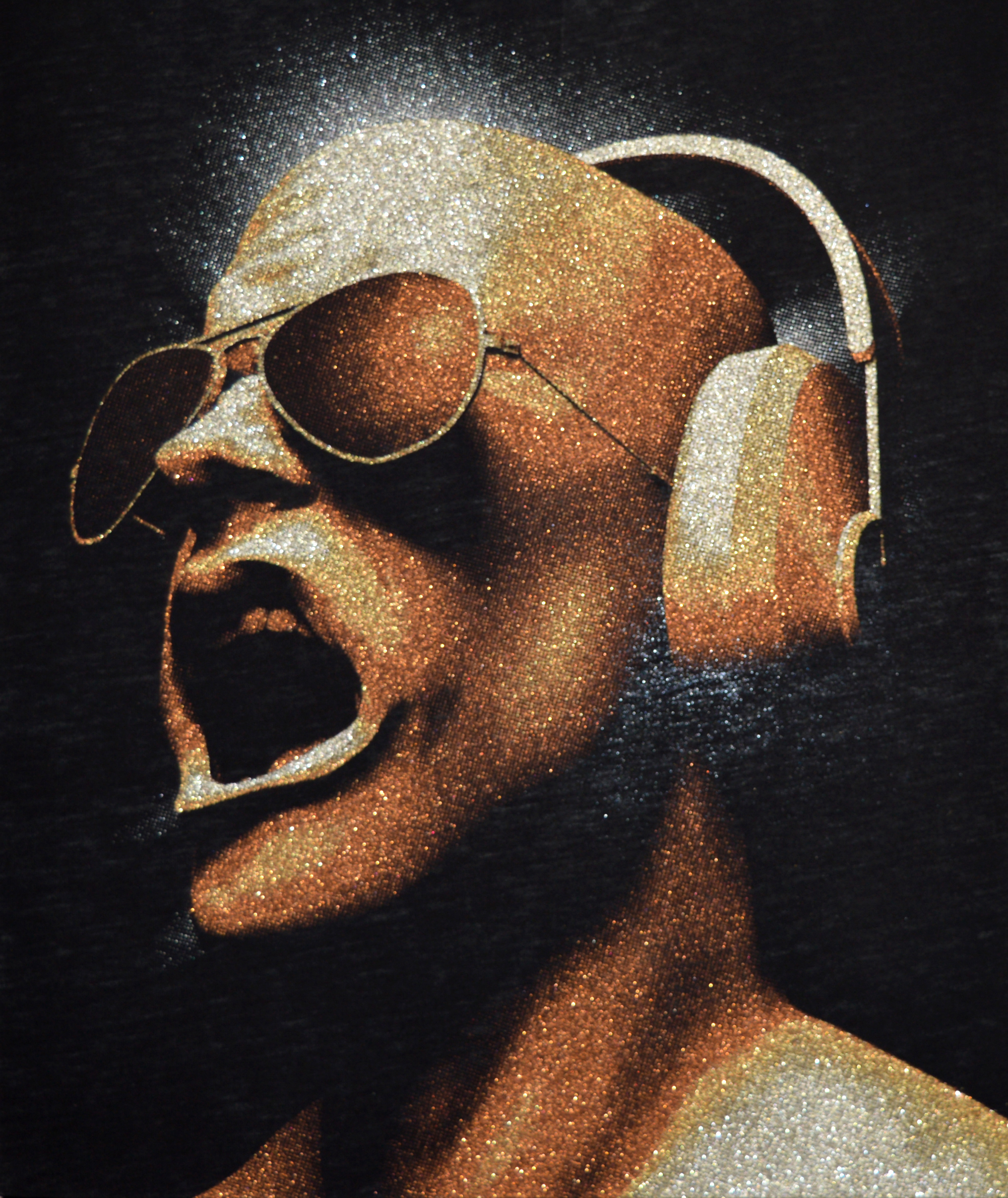

Printed with water-based inks, glitter, three-color, and halftones. Photo courtesy of Virus Inks.

Discharge

Discharge ink is another type of water-based ink that works through a chemical reaction with the dyed cotton fibers. Unlike traditional water-based ink, discharge has a few extra ingredients and a discharge agent that’s mixed into the ink that causes the ink to extract the dyes in the fabric fibers, returning them to their natural color, usually a brown shade. The discharge process takes place in the dryer. The print won’t look great when it’s removed from the press platen, but it looks great after it’s properly cured.

There are two different discharge agents you can use. The most popular is zinc formaldehyde sulfoxylate (ZFS) and it’s by far, the most effective at extracting the dyes. However, ZFS emits formaldehyde gas during curing so adequate ventilation in the workspace is needed. A newer discharge agent uses thiourea dioxide. In both systems, the ink has a limited life once the discharge agent is added, usually between six and eight hours. Discharge prints have a superior hand feel compared to all other apparel screen print inks, almost as if the print is part of the shirt. You can also use discharge inks as an underbase, and print plastisol colors on top to reduce the hand feel, as well. One final thought regarding discharge prints: The customer should know the shirts should be washed before wearing them to avoid skin irritation.

Pros/Cons of

Water-Based

The biggest (customer-facing) advantage to using water-based inks are the soft print results achieved. The ink penetrates the fabric fibers instead of sitting on top like plastisol, and customers love the soft feel. There are no harmful or toxic chemicals or components in water-based inks, so they’re safe to work with and wear. Some will argue this point when discussing the ZFS in discharge inks, but that’s another article.

One disadvantage of water-based inks, especially discharge, is the ability to match colors. Exact matches using discharge inks aren’t guaranteed due to the varying differences in how fabrics are dyed. Each brand of T-shirt will discharge slightly different, and results can vary between brands or even fabric colors within the same brand. Only cotton fibers can be discharged. Synthetic fibers such as polyester, rayon, and spandex cannot be discharged.

Do’S

- Leave screens flooded.

- Use spray bottles and water to mist inks regularly.

- Use a water-resistant emulsion.

- Properly expose screens to improve press longevity.

- Only mix what’s needed when using discharge inks; they have a limited pot life.

- Preheat your platens before your production run.

Don’tS

- Overfill ink in the screen; keep an amount suitable for printing and refresh often.

- Let the ink dry in open areas of the screen; print then flood as opposed to flood then print.

Variables of Curing

Following are recommendations for managing the variables and ensuring you achieve proper cure for any ink you use. Successful curing goes beyond the ink and its cure temperature.

Fabric Potential

to Absorb Moisture

A garment’s fiber content determines its ability to receive, absorb, and disperse heat. This ability plays a key role in determining how quickly the moisture within the garment fibers can be driven out. Polyester garments are hydrophobic. They don’t absorb moisture and will reach temperature quicker than 100-percent cotton garments, which are hydrophilic and absorb moisture. Make sure you understand the properties of garments you decorate.

Because higher fabric moisture content requires longer exposure to heat, you should monitor your shop’s humidity, test for proper cure on a regular basis, and make necessary adjustments to dryer settings as the environment changes. Humidity changes can occur between morning and afternoon, or from season to season. If you do suspect high moisture content within the garments, pass them through the dryer prior to printing. If moisture is not driven off, the ink may have difficulty reaching proper cure.

Water-based, high-density print. Photo courtesy of Virus Inks.

Fabric Weight,

Construction, and Color

Fabric construction plays a key role in determining the ink deposit that’s required for acceptable print detail. Fabrics with higher stitch densities provide a smoother surface for the ink thus requiring a thinner ink deposit. Lower stitch counts are less dense and require a thicker ink deposit to achieve acceptable coverage.

Fabric weight is controlled by thread size and by the number of stitches per inch. Heavyweight cotton garments will require longer oven times to drive off moisture due to the additional mass of the garment. Fabric color must be considered, as well. When using infrared dryers, dark colored garments absorb heat more quickly than light colored ones and they also absorb and disperse moisture more quickly.

A wash test ensures that printed samples are subjected to standard home-laundering practices. Recommended equipment includes a large-capacity washer, a large-capacity dryer, and a total load weight of around four pounds. To conduct a wash test, cut a printed sample in half. Place half of the sample in the washer with the additional items (T-shirts, bath towels, etc.). Use a medium load, hot wash/cold rinse water setting, and a commercial concentrated detergent (i.e., Tide, All, Cheer, etc.). After washing is complete, place the sample and additional items into the dryer. Set the dryer to a Cotton/High (105°F/40°C) setting and dry the load. Perform at least five laundry cycles; then compare the washed half of the sample with the unwashed portion. If severe cracking of the ink or partial or total loss of the ink film from the garment is noted, the ink is not cured.

While there are many different types of screen printing inks available to apparel decorators, each has a specific purpose and recommended use. Fiber type dictates ink(s) suitable for use when printing, so work with your ink suppliers to learn about the different types and chemistries they offer. Above all, think twice and print once (to steal from an old carpenter phrase) so your hard work to make a profit doesn’t turn into rags.

For more insight on screen printing inks, check out these articles from Family Industries on screenprintingmag.com.

PHOTO GALLERY (14 IMAGES)

Advertisement

SPONSORED VIDEO

Let’s Talk About It

Creating a More Diverse and Inclusive Screen Printing Industry

LET’S TALK About It: Part 3 discusses how four screen printers have employed people with disabilities, why you should consider doing the same, the resources that are available, and more. Watch the live webinar, held August 16, moderated by Adrienne Palmer, editor-in-chief, Screen Printing magazine, with panelists Ali Banholzer, Amber Massey, Ryan Moor, and Jed Seifert. The multi-part series is hosted exclusively by ROQ.US and U.N.I.T.E Together. Let’s Talk About It: Part 1 focused on Black, female screen printers and can be watched here; Part 2 focused on the LGBTQ+ community and can be watched here.

You may like

Advertisement

Inkcups Announces New CEO and Leadership Restructure

Hope Harbor to Receive Donation from BlueCotton’s 2024 Mary Ruth King Award Recipient

Livin’ the High Life

Advertisement

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Screen Printing magazine's news bulletin.

Advertisement

Most Popular

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Case Studies1 month ago

Case Studies1 month agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Andy MacDougall1 month ago

Andy MacDougall1 month agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns2 weeks ago

Columns2 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?