Articles

Published

24 years agoon

Artist and professor Malaquias Montoya has used screen printing as a medium for social change since his first position 40 years ago in a San Jose, CA, commercial art and sign shop. Now a professor of Chicano studies and a cooperating faculty member in the art department at University of California-Davis, Montoya is renowned as an award-winning printmaker whose art, activism, and teaching have created both social and art history.

Credited by historians as one of the founders of a “social serigraphy” movement in the San Francisco Bay Area in the mid-1960s, the celebrated poster-maker and muralist started out like any young screen printer. Montoya produced political campaign banners and point-of-purchase signs for Ed Pranger’s Commercial Art and Advertising back in the days when printers rarely considered using gloves to protect their hands from chemicals and solvents.

“We used lacquer hand-cut stencils and photo silkscreen methods to make stencils,” Montoya recalls. “Our screens were of silk, but I changed to nylon and then polyester and other handmade fabrics as they came out. Silk changed with the atmosphere: you’d stretch a screen at night, but the weather could alter it by morning.”

It was the pre-MSDS era, so Montoya would identify the solvents on cleaning rags by sniffing at them. He developed stencils with potassium dichromate, and reclaiming was done with full-strength bleach. “I had a lot of problems with skin rashes, and my hands were often cracked and dry,” he says. But the young screen printer loved his work.

From hardship comes inspiration

Born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Montoya grew up as a migrant farm worker. Screen printing was his first indoor job. “I used to look at the ads in the paper, and I remember how excited I was by an ad that said ‘Printer Wanted. 8 to 5. Monday through Friday.’ I had never had a job that went 8 to 5 and gave you weekends off.” During his interview at Pranger’s, he was asked to work for one month at no pay as an apprentice, and he happily agreed. But by the end of the month, Montoya had performed so well that he was paid the regular $1.15/hour wage anyway.

Montoya landed the screen-printing job in 1962, on the eve of a volatile period in American cultural history. Small matters like sore hands or aching shoulders did not dissuade the young man from returning to the shop after hours to donate time and design talents to San Jose’s Mexican-American community. This generous action initiated a lifetime of creating the kind of art German poet and dramatist Bertolt Brecht imagined when he said, “Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.”

His after-hours work included political-issue posters and event announcements for the local Chicano population. He was building the foundation for what was to become a renaissance among Chicano artists. Montoya’s socially-motivated screen prints fueled the cause of Mexican-American laborers and farm workers, tying it into the national civil rights movement of the mid-1960s.

Because of his intimate knowledge of the migrant farm workers’ community, Montoya felt a strong connection to the struggles of his people. Montoya was one of seven children whose parents could neither read nor write Spanish or English. After his parents divorced, he was raised primarily by his mother, Lucia, who toiled long hours in the fields to assure her children an education.

The children would start school late each year after helping with the harvest. “By the time we started, many of us were shy and timid,” says Montoya, explaining how beginning late each year drew unwanted attention from teachers and classmates. “And if you had a name like Malaquias it was even worse, because nobody could pronounce it.”

While he clearly didn’t lack thinking and learning abilities, Montoya was forced to repeat the third grade in a class for developmentally challenged children. Because English was their second language, he and other Chicanos were looked upon as “slow.” Still, he sees the experience as positive .

“I was fortunate to be in this class, because all we did was art work. We drew, made collages, and glued pieces of wood together. For me it was a very warm atmosphere with mostly Chicanos/Mexicanos, some black kids, and also migrant workers from Oklahoma and Arkansas. We were called retarded and other names by the other kids, but artwork became a place where I could draw friends or teachers who hurt my feelings. I enjoyed it very much–it was another way of expressing myself. I was able to discover creativity.”

Montoya’s natural artistic talents quickly became evident to teachers and peers and helped move him out of the “slow” class. His reputation as an artist preceded him, and students doing class projects often sought him out for his abilities, which gave him a feeling of importance. “When people asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up,” says Montoya, “I knew I couldn’t say I wanted to be a doctor or a lawyer, because you had to be smart. So I said I wanted to be an artist and got pats on the back.” That experience and others developed into a profound and principled moral system that found its expression in screen-printed art and in murals.

“I saw a lot of injustice, and those things helped me form an ethical sense,” he says. “I remember working in the fields as a boy, which was very hard, and wondering about religion. We were brought up Catholic, and I’d ask my mom, ‘If we are all Catholics, and God loves Catholics, why are we out here working so hard?’ And my mom would say ‘That’s the way God wants it.’ But I remember the way the ranchers treated the workers. I remember the way the grocers treated my mother because she bought groceries on credit. My mom tried to answer in her broken English. I would just sit there and burn.”

These values figure strongly in Montoya’s imagery as a poster and printmaker and muralist, and in his work as an educator. In addition to donating many hours of service to schools, cultural groups, and social organizations, Montoya has spent many years training printers in a master-apprentice program that teaches the use of screen printing as an inexpensive reproduction method for communicating social issues. In his program, students learn solid technical skills by developing and printing images to promote a cause or organization that interests them and benefits their community.

Montoya also has developed a successful career as a professional graphic artist, producing logos for community centers and political organizations, as well as calendars, prints, and posters. And with his wife Lezlie Salkowitz Montoya–a ceramic artist and photographer who also teaches in a children’s computer classroom–he prepared color separations for an anthology of short stories produced in collaboration with young students at a bilingual school.

While widely recognized as a fine artist, Montoya has avoided the rarefied world of private collectors and galleries. “I don’t do a lot of paintings, because [a painting] is only one of a kind. So when I do a painting, it’s usually for my wife’s birthday or a gift.”

In an artist’s statement, Montoya explains why he steers away from using his art for self-aggrandizement: “I attempt to communicate, reach out and touch others, especially…that silent and often ignored populace of Chicano, Mexican, and Central American working class, along with other disenfranchised people of the world.”

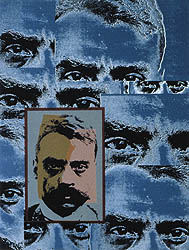

Screen printing has allowed him to communicate across the widest possible spectrum of community activism, as his images illustrate (Figures 1-6). One of his first after-hours posters advertised a walkout of Chicano graduates at San Jose State University in 1968.

“This was a time of great political struggle for civil rights, and I remembered what things had been like in my own life,” he explains. “I had compassion for what black Americans were going through, and I thought my experience as a farm worker had been easier than theirs. And then the Caesar Chavez movement [for fair treatment of farm laborers] began. I get choked up thinking about it now. I became very involved.

“I never looked at my work as political; I was painting or drawing my experience, which is what I knew best. When the farm worker struggles started happening, I wanted to depict that because it was so close to me and my family. We had worked in the fields, and I knew there were injustices there. Caesar Chavez was articulating them in a very moving, profound way. Now when I drew something, I knew why: I was communicating something very close to me and important to me.”

Mastering his art

Montoya worked at the commercial screen-printing shop for five years, perfecting the techniques he would use to create the poster imagery for which he is best known. He went on to become a shop foreman in a printed circuit-board facility and then focused on his education.

He was trained in commercial and fine art, first at a local junior college and later at San Jose City College, where his sign-shop employer had asked him to take some commercial-art courses. This is where he met an art professor who became a lifelong admirer and mentor.

Professor Joe Zirker offered Montoya a new perspective on the world of fine art. Not only did Zirker introduce Montoya to the works of important Mexican artists like Diego Rivera, Jose Clement Orzco, and David Alfaro Siquerios, he encouraged the young artist to continue to develop the fluid illustrative style that both Montoya’s sign shop employer and commercial-art professor disliked.

“I was sent to take a drawing class from Joe after being told that my drawing was terrible” Montoya says. “But Joe looked at my college drawings and said they were fantastic. That was the beginning of my realization that I could become a fine artist.”

Strengthened by this reinforcement and by study of his own cultural history, Montoya went on to earn a Bachelor’s Degree in art from the University of California, Berkeley. It was here that Montoya and his brother, José Ernesto Montoya, a poet and retired CSU professor, founded the Mexican-American Liberation Art (MALA) Front. Joining them were Bay Area artists Manuel Hernandez-Trujillo, Esteban Villa, and Rene Yañez.

Probably the most influential Chicano art coalition in the civil rights movement, the group met weekly to discuss the role of the artist within what was known as El Movimiento. In discussing each other’s work, they discovered common experiences with oppression, and the group grew to involve 20-30 people, including visual artists, poets, and young writers.

Montoya had been unmoved by his studies of contemporary art, and once he and the others began studying Mexican artists, they realized what they had been missing in college. “We realized we could use our art to speak about our conditions. It was an incredible awakening for me. All these years in college, I began to know what I wanted to say, but when I tried to say it I was told it was bad art.”

The group gathered strong community support when its work began depicting people with distinctly Mexican features. “This came out of discussions about times we had wished we weren’t Mexican,” explains Montoya. The group’s work began to include pre-Colombian images in a style previously seen only in Mexican restaurants. “They were bad reproductions,” says Montoya, “but we were starting to look at them in a whole different way.”

In the first MALA-Front exhibitions, Montoya and his fellow artists modeled the imagery on a young poet named Manual Gomez. “He had a face like…one of the images of Mayan sculpture.” says Montoya, “So the entire show was about this new young face. It focused on our pride in this face that we had once thought ugly, and it suggested that we should be proud of how we looked.”

It was an extremely successful exhibition, well attended by the people Montoya had hoped would see it. “They were our people, and they were looking at themselves, at this image of an Indian,” he recalls. “Everyone from college students to the winitos on the street corner were there talking about art. We showed the work, not in an effort to sell it, but just to present this new image.” Coupled with this artistic endeavor were the artists’ political aims. They were activists trying to improve the conditions of their people, and screen printing was a very practical tool.

Montoya’s poster work continued to gain a wide audience, and he also became involved in a mural movement when he and other artists were hired to paint imagery inspired by Mexican life and iconography in schools and public places. This blending of art and social consciousness grew into community workshops where Montoya and fellow artist Manuel Hernandez endeavored “to teach children and others how to make art.” The workshops, which focused on screen printing as a tool for social communication, continued successfully into the 1980s.

After Montoya graduated with honors from UC Berkeley, he became a lecturer in the Chicano studies department there. He was later a faculty member in Berkeley’s University Without Walls, where he continued screen-printing workshops. He moved on to teach art at various Bay Area colleges before becoming a tenured professor at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland in the early 1980s. He was hired to a full professorship at UC Davis in 1990.

Ideals for the here and now

Today, Montoya’s resume of credentials, honors, and accomplishments extends for 35 pages. But Montoya has no intention of resting on his laurels. Although a denizen of the academic world, he refuses to become involved in the competitive and profit-driven world of juried exhibitions and art-gallery representations. Instead, he remains dedicated to screen printing as a social hammer.

“There’s a lot of so-called political art that is part of the mainstream in galleries today,” Montoya comments. “My feeling is that as long as it stays within the art community, it doesn’t have an effect on anything but the artists themselves. I always feel that action has to come from the bottom up.” Consequently, Montoya continues to exhibit almost exclusively in public places: hospitals and clinics, university galleries, and community centers. He also continues to develop poster designs for worthy causes and for nominal pay.

He teaches students to follow a similar path. The syllabus from his “Introduction to Silkscreening” course, taught most recently at the University of Notre Dame where he was a visiting scholar last spring, invites students to understand not just the techniques of making a screen-printed poster, but “the philosophical underpinnings of art and the social environment [where] it occurs.”

Montoya has written that “through our images we are the creators of culture, and it is our responsibility that our images are of our times–and that they be depicted honestly and promote an attitude towards existing reality; a confrontational attitude, one of change rather than adaptability–images of our time and for our contemporaries. We must not fall into the age old cliché that the artist is always ahead of his/her time. No, it is most urgent that we be on time.”

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Screenprinting Magazine.

Most Popular

-

Case Studies2 months ago

Case Studies2 months agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns3 weeks ago

Columns3 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

News & Trends2 months ago

News & Trends2 months agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?