Articles

Balancing the Risks and Rewards of Adopting an Innovation

Published

6 years agoon

In our special Innovation Issue, we present a collection of expert essays on an important technology in the industry today. In his special edition introduction, Mark Coudray discusses the process of innovation.

In our special Innovation Issue, we present a collection of expert essays on an important technology in the industry today. In his special edition introduction, Mark Coudray discusses the process of innovation.

Innovation is racing ahead at a maddening rate. It’s a challenge to know if a new technology is mature enough to purchase and actually reap the benefits preached by the salespeople. I’ve always been on the bleeding edge of technology and have been burned more times than I’d like to admit. (I once had a drum scanner that almost became my $250,000 doorstop.) Each new technology that emerges is great in theory, but as they say, the devil is in the details.

It occurred to me that it would be helpful to provide some perspective about innovation so you can make decisions about new technology with more confidence. It turns out businesses have been struggling with this issue for more than 300 years.

The problem began to gain momentum with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, when the economy made a major shift from agrarian to industrial mechanization. The printing industry was right in the middle of this as presses evolved from hand-driven to mechanized. This shift is being repeated again as we move from an analog economy to a digital one. The only difference: Today’s transition is happening exponentially faster.

AdvertisementThe Challenge

Here’s what we’re facing: Innovation is happening at a continuous rate. Products are now developed using the Agile Model, a concept that came from the software industry that describes a product being coded up to and after its release. The production process starts before the final product is even completely designed, which is something everyone needs to realize when making tech acquisition decisions, as we’ll see.

Design iteration is happening as the market develops and as buyers respond to the initial marketing of the new technology. Some of the ideas are so new and different that there’s nothing to compare them to. This makes it extremely difficult to decide whether or not to adopt them.

Two good examples are the iPhone and the iPad. Both of these products changed the behavior of the user and enabled a wide array of new apps, activities, and uses. Before these devices, consumers were perfectly happy with the “dumb” phones and laptops they were using.

Another challenge is simply not having enough time to research and learn about new software and technology. Gone are the days of having six months to learn a new operating system. The exponential expansion of knowledge is making it almost impossible to keep pace. This has spawned “design thinking,” where the focus is on the user experience and user interface. Designers toss around words like intuitive and transparent to describe how easy the technology is to adopt and learn.

This situation is compounded by extremely short product development cycles of 9 to 24 months driven by the price/performance relationship described in Moore’s law (named after Intel founder Gordon Moore), which states that each new cycle brings faster processing at lower cost. If you are an early adopter, you:

1. Pay a high price.

2. Face a steep learning curve.

3. Need to educate your customers and sell the value of the “new” way.

4. Deal with unreliable production.

5. Suffer frequent, expensive breakdowns that may be difficult to find someone to fix.

Sound familiar? In the wide-format industry, there are a number of legendary tales of technicians who essentially lived in the plants where new printers had been installed. Making this set of challenges more formidable is that fact that competitors who enter the market after you can buy faster, more stable, and better equipment at a lower cost.

The Innovator’s Dilemma

Being the first to have a true innovation, even if the product is half-baked, allows you to carve out and gain new market share since there is little, if any, competition. The downside is a longer sales cycle as you spend more time educating your customers on the features and benefits of the new technology. This delay burns into the life cycle of the current generation of technology you’re working with.

Buyers have a natural reluctance to jump on board. After all, they have no point of reference. From a strategic perspective, it helps to position your new offerings as being just beyond what’s currently available and commonplace. If the technology seems too far ahead, customers are likely to react conservatively; not far enough ahead and they won’t see the obvious advantages of what you’re suggesting.

You can wait until the price of the technology comes down and is on a more stable platform, but that has its costs as well. Delay means you’ll be fighting for market share. As any technology becomes more common and accessible, the price drops and the advantages become commoditized. This happens first in the larger markets and eventually filters down to the small markets and cities.

So how do you approach the question of when to take the plunge? You have several options. The first step is to fully understand the innovation cycle and how a new technology fits in, and the second is to understand how technology is adopted and what pattern makes sense for you.

The Innovation Life Cycle

Every technology goes through four distinct phases. The same steps apply to the life cycle of any philosophy, political structure, religion, or society, but we’ll stick to technology here.

The first phase is true innovation. You and I know it as “the next big thing,” where a brand new idea is invented. These types of breakthroughs are very rare. Almost all ideas are derivatives of previous discoveries.

True innovation is a very dangerous place to be because there is almost always no infrastructure in place to make the technology work to its full potential. When Edison invented the incandescent light bulb, there were no centralized sources of power, distribution lines, or houses with electrical wiring, plugs, or receptacles. There were no fuse boxes or circuit breakers to protect from overload. There were no portable generators. In short, you could not make the invention work outside of the laboratory.

This brings us to the next phase, extension. This phase begins with infrastructure developments needed to support the original invention. Think of charging stations for electric vehicles or, in our world, pretreatment applicators for DTG printing. Once these elements are in place, this phase gets into the territory where most of us are comfortable – faster, better, cheaper, as the technology grows and is adopted. This phase is where most purchases of the technology are made, and it can last decades or longer. The life cycles are shorter in the digital age, but can still be substantial.

The third phase is called substitution. This is where the original invention is now replaced by improved technology that may work differently, but still delivers the same result. In the case of the incandescent light bulb, substitution happened with compact florescent bulbs followed a few short years later by LEDs. In each case, the energy consumption dropped significantly as well as the toxic disposal concerns.

Substitution signals the downward slope of the life of the invention. Extension can still occur here, significantly extending the life of the technology. Unfortunately, this is the current phase for screen printing. It still has applications and always will, but in some sectors, such as wide-format graphics, it is being substituted by inkjet. In other sectors, like garment printing, it is being hybridized with digital to extend the life of screen.

The fourth and final phase is demise. This is where the original invention has become irrelevant, or is no longer functional, or has become economically uncompetitive. Millions of innovations have cycled out. Ultimately, everything reaches this point, as long as we keep innovating. With the light bulb, OLED panels or surfaces will eventually render the light bulb irrelevant, adding new capabilities way beyond light emission. Think of the holodeck from “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” where you could sit by a mountain lake or immerse yourself in a dynamic virtual reality set.

The Diffusion of Innovation

Something we are all very familiar with in this day and age is the process of technology moving into our lives. Think of how technologies such as the internet, smartphones, and, in our industry, large-format digital printers were integrated. This concept is called the diffusion of innovation, a term coined by Everett M. Rogers in 1962 to explain how an idea, product, or technology gains momentum and spreads through a specific population or social system. His landmark book “Diffusion of Innovations” is a must-read for anyone facing the adoption of technology and the associated organizational change; it inspired another excellent book by Geoffrey A. Moore, “Crossing the Chasm.” Both explain which parts of the population adopt technology and at what rate.

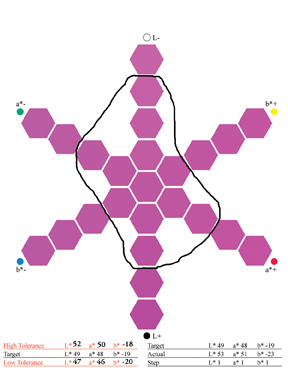

Adoption falls into five distinct groups. Let’s take a look at each so you can determine where you currently reside and what this means for you.

Innovators

These are the geeks, nerds, eggheads, and academics. They typically don’t interact well with the general population. They’re considered “way out there” by their friends and colleagues, until their inventions catch on. (Then they are thought of as visionaries.) They are so intently interested in the technology that they could not care less about what everyone else is doing. Innovators represent 2.5 percent of the population.

This group is also known as “alpha adaptors.” They are the first in and often are more interested in tearing apart the new thing than using it or making it work. Generally, they have minimal, if any, interest in the commercial elements or the economic justification of the invention. They fully expect the invention to break and they further expect that they will fix and improve it.

Many members of this group are engineers and frustrated inventors. They enjoy tinkering and tweaking. They embrace the possibilities of the innovation, but fully recognize the current version is nowhere near capable of reaching its full potential. They are all about proof of concept. We often refer to them as the pioneers with the arrows in their backs.

Innovators are very useful to the creators of the idea or technology. They speak the same language and can provide highly technical feedback that results in the evolution of the invention to the next level.

Early Adopters

Representing 13.5 percent of the population, early adopters can be thought of as the more advanced beta testers. At the beta stage, the idea or technology is ready to be field tested, but still not ready for prime time. It’s not stable and hasn’t been fully vetted across all possible conditions.

Early adopters are a very interesting group. In high school, they were the cool kids, the ones who had the newest gadgets, wore the latest fashions, and listened to the hippest music. They hung around in cliques and had a certain sense of superiority bordering on arrogance. In short, they were “in the know” on everything.

In the real world, early adopters are the influencers – thought leaders that peers look up to. They have a reputation for being out in front, understanding what they are doing, and most importantly, being able to explain to others what the new technology is all about.

Early adopters expect the technology to work most of the time. If it breaks, they’ll appeal to one of their nerd friends to fix it. They’ll complain about reliability, but will be satisfied or placated with a discount as the price of access to the new technology.

These first two phases typically take one to two years before reaching a holding pattern known as the “chasm.” This is the term Moore used to describe the 9 to 18-month period before the next level begins buying. Gartner, Inc., a well-known consultancy and analytics group, has termed this stage the trough of disillusionment. It’s where the technology either engages or dies.

Early Mainstream

This is where the technology reaches escape velocity. It is characterized by multiple entrants into the market introducing bigger, faster, better, or cheaper options – in other words, the extension phase. The early mainstream represents 34 percent of the market. Growth at this stage is characterized by the classic hockey stick curve.

The early mainstream has taken a wait-and-see approach. They have justified to themselves that the technology is worth investing in. They also know they can sell it to their customers with little resistance. This is largely because the customers have heard of the technology, but haven’t experienced it personally. They trust their vendor and go for it.

Early mainstream adopters are also the companies that have waited for the price to come down along with the risk. They fully expect the offering to work right out of the box, and they have little tolerance for startup difficulties. They are very vocal and upset when the product doesn’t work, and they’re not afraid to let everyone know about it.

During this phase, the technology is growing rapidly, maturing, and being extended by well-funded competitors who are in it for the long haul. When mainstream corporations begin marketing heavily, you know you’re in the growth phase trending to the maturation of the technology.

With everything considered, the buyers in the early mainstream are only marginally profitable. This is due primarily to the capital costs, adoption and training expense, competition, and inefficiencies of use. Well-run companies in this segment can be very profitable. Marginal companies will have marginal results.

Late Mainstream

The late mainstream represents the peak of adoption, the place in the development cycle when substitution begins. These adopters are late to the game but still represent 34 percent of the population. These customers are looking for deep discounts on their purchase. They are happy to buy used equipment, as long as it comes with a guarantee and works.

Late adopters have no tolerance for things that don’t work or aren’t immediately productive. They don’t like change and are only buying because they have lost their edge in the market. Their competition has forced them to act, which they’re doing, but for the lowest possible investment. They are often happy with versions that are one or two generations old.

If they buy used, they buy at a fraction of the cost of new. This gives them a competitive advantage and they are often very, very profitable. They don’t care about being flashy or on the cutting edge. They would rather have the money in the bank.

Laggards

From the technology developer’s perspective, this group is not worth spending time on. They are highly resistant to change and live at the end of the technology life cycle. They will often be so resistant to change that they are the only ones left using a technology or process. They represent 16 percent of the market, mirroring the same percentage as the innovators and early adopters combined.

Like the late mainstream buyers, laggards are highly profitable since their capital costs are so low and fully depreciated. They are always looking for cheap or free. They will often haul away old technology, fix and refurbish it, and have a reasonably productive piece. They are reluctant to buy anything and would never buy anything new.

They service a part of the market characterized as low-end price shoppers who are satisfied with just getting by. This is exactly what the laggards deliver, so everyone is happy. Their customers are not going to pay higher prices from other vendors who have more modern technology. Price is their primary advantage.

Know Your Position

Understanding the innovation cycle and adoption phases will help you to determine your comfort zone when it comes to assessing and purchasing new technology. It is also very helpful in assessing your competition and identifying factors that will be crucial to success after the purchase. Being able to determine your risk tolerance takes some of the anxiety and stress out of evaluating new investments and deciding when to make them.

Read more from Mark A. Coudray.

SPONSORED VIDEO

Let’s Talk About It

Creating a More Diverse and Inclusive Screen Printing Industry

LET’S TALK About It: Part 3 discusses how four screen printers have employed people with disabilities, why you should consider doing the same, the resources that are available, and more. Watch the live webinar, held August 16, moderated by Adrienne Palmer, editor-in-chief, Screen Printing magazine, with panelists Ali Banholzer, Amber Massey, Ryan Moor, and Jed Seifert. The multi-part series is hosted exclusively by ROQ.US and U.N.I.T.E Together. Let’s Talk About It: Part 1 focused on Black, female screen printers and can be watched here; Part 2 focused on the LGBTQ+ community and can be watched here.

You may like

Advertisement

Inkcups Announces New CEO and Leadership Restructure

Hope Harbor to Receive Donation from BlueCotton’s 2024 Mary Ruth King Award Recipient

Livin’ the High Life

Advertisement

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Screen Printing magazine's news bulletin.

Advertisement

Most Popular

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Case Studies1 month ago

Case Studies1 month agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Andy MacDougall1 month ago

Andy MacDougall1 month agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns2 weeks ago

Columns2 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?