Articles

Fine-Art Face-Off

Published

20 years agoon

Serigraphy

Serigraphy is the romantic island in the big sea of screen printing. Even though serigraphy studios use techniques similar to those found in commercial graphics shops, fine-art specialists focus more on craftsmanship than throughput. A high-volume display-graphics printer may rely on automatic presses, while a serigraphic atelier (pronounced at-el-yay and loosely defined as an art/design studio) concentrates on creating prints by hand and uses what the big shops might describe as simple tools. Some serigraphy studios own just one or two presses.

One such studio is San Francisco, CA-based Golden Gate Editions. Lori Dodge, general manager, says that while there are serigraphy shops that have fully automatic presses, she believes creating hand-printed editions is the only way to keep waste low, prices down, and print registration on track. “We’re a boutique studio,” she says. “We’re not out to mass market.”

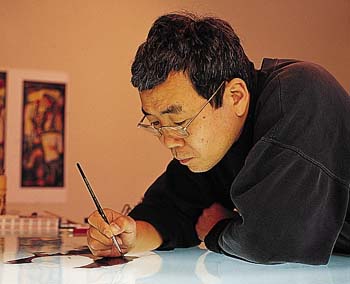

Once Golden Gate accepts a job, the artist will come in to discuss the fine points and possibly participate in painting the acetate films used in screenmaking (Figure 1). While each project is handled as a full-time job until it’s complete, it still takes one to two months to produce an edition.

Explaining the lengthy process, Dodge points out that Golden Gate mixes its own inks by hand using base and pigments. Colors are matched to the original the old fashioned way–by sight. The studio’s master chromist, Tetsumi Minoh, uses his eyes and 25 years of experience to ensure the accuracy of each color that passes through Golden Gate’s screens. Fortunately, artists and art publishers who work with Golden Gate understand that serigraphy is a time-consuming and often costly process. Most are more than happy to wait for the end results.

AdvertisementGiclée

Giclée might sound refreshing to those who spend their days watching wide-format inkjet printheads shuttle across banners, fleet markings, and other graphics. Giclée takes familiar digital-imaging technology–scanners, graphics software, and inkjet printers–and applies it to fine-art reproduction.

Giclée’s roots begin with the Iris printer (Figure 2), an inkjet device most commonly associated with producing continuous-tone color proofs. Today, improved technology has swelled the ranks of fine-art inkjets to include wide-format models from Roland, Mutoh, Epson, Mimaki, MacDermid ColorSpan, and others.

Despite advances in digital-printing technology, some giclée producers are not quite satisfied with the way their inkjets perform out of the box. Jon Cone, president and master printer at Cone Editions, East Topsham, VT, re-engineers his Iris printers, modifying their hardware and creating his own imaging software in order to increase ink output, achieve greater color saturation, and ensure compatibility with his proprietary inks.

Originally a serigrapher, Cone cites changes in serigraphic inks as one of the primary reasons for his move to digital technology. “I chose to go into digital because I saw it as a viable medium and I saw the writing on the wall that, eventually, my favorite serigraphy materials would be unavailable,” Cone says.

When an artist contacts Cone Editions about a giclée job, the studio evaluates the work and determines whether it can achieve the desired results with existing inks, software, and paper. If the job can be completed without any experimentation, Cone Editions will capture the image with a high-end drum scanner, edit the digital image to remove any dust or scratches, and finally generate a proof. “Within two weeks, we usually have a very clean proof to send the artist,” he says.

AdvertisementCone stresses the importance of generating new proofs when orders for additional prints are made. “Inks and papers do change from batch to batch from the manufacturers–sometimes it’s subtle, sometimes it’s not so subtle,” he explains. “So we make a proof again and we match it against the proof we have on file. If it doesn’t match, it’s the artist’s responsibility to pay us to make it match.”

Benefits and drawbacks

Both serigraphy and giclée have their selling and sticking points. An artist’s or publisher’s decision to go with either technique is often based on a mix of factors–some concrete and tangible, some subjective and abstract. These factors typically include cost, job turnaround, inventory, permanence, aesthetic quality, and overall accuracy. Some clients may value certain aspects of serigraphy or giclée, while others may place those same aspects on a pay-no-mind list.

Serigraphy This classic method of fine-art reproduction involves labor- and materials-intensive processes, especially in prepress where procedures include mesh stretching, coating, and stencil exposure and developing. A single job could involve just five screens or more than 105. Each of those screens has to go through similar prepress treatments in order to perform as planned, which contributes to serigraphy’s slow turnaround time.

Serigraphy is expensive. Aside from the labor and materials involved in printing, the price tag reflects the craftsmanship and talent that a studio’s personnel puts into each edition.

So what’s attractive about reproduction that can cost well into the five-figure price range and take months to complete? Color quality (Figure 3) is one thing. “With serigraphy, you can make the exact color and the exact brilliance you want,” says John Shaw, former managing director, Digital Printing and Imaging Association. “You can do things with a screen ink that are not exactly replicable with a four-color [digital] process.”

AdvertisementAlong similar lines, Dodge says that, when comparing prints made with both processes, viewers find that the serigraphs are richer and carry more texture because each color is put down one at a time. She explains that giclées are often embellished–painted over or screen printed–to give the appearance of thickness. “A giclée is a photocopy,” she says.

Even Jack Duganne, founder of Duganne Ateliers–the man who many credit with coining the term giclée–says he loves serigraphs. “They’re incredible,” the former serigrapher says. “In cases where you’re dealing with really beautiful graphic imagery, there’s nothing like it. Nothing can touch it.”

Serigraphy does not lend itself well to a print-on-demand workflow. All prints are produced in a single period. That’s the most logical and least wasteful way to print serigraphs because the screens can be prepared and the inks mixed at the same time.

But having an entire edition to maintain can be a daunting task for some artists and publishers because new variables enter the picture: How will the prints be stored to ensure their safety and longevity? Will the prints require insurance? What if the edition doesn’t sell out? How many serigraphs will need to be sold in order to break even on the investment? These issues–and the desire for faster turnaround and lower costs–are what drive many artists to giclée.

Giclée The black sheep of the “high-art market” is a white knight for artists who have yet to connect with publishers, are on tight budgets, or want to sell small editions. Thanks to the print-to-order nature of digital imaging, it’s feasible for an artist to have a single giclée print made, display it at a show, and then give prospective buyers an idea of when their own copies could be printed, signed, and shipped. The same benefit is available to artists looking to connect with a few galleries or art reviewers. For these individuals, the relative economy of giclée provides the opportunity to spend a little and potentially gain a lot of exposure.

Giclée also saves time. Fine-art digital printing comprises just three steps: image capture (scanning), image editing and color correcting (Figure 4), and printing. “The first proof can appear within two hours,” Cone says. “And for $200-250, the artist can see where the project is.” Part of this efficiency, he explains, is due to the improved color-matching capabilities offered by giclée producers.

The economy of giclée is often blamed for the flood of digital reproductions that has hit the fine-art market. “Galleries don’t respect giclées anymore,” Dodge claims. “If they get a giclée in a tube, I don’t think they’d take that artist too seriously–they’d want originals to begin with.”

Further muddying the water is the fact that, with a minimal investment, people can generate giclées at home. However, Cone points out that even though the output technology is affordable and readily available, the key is in the ability to scan and correct colors. “We have a $100,000 drum scanner, while a person at home has a $300-400 scanner,” he says. “They have the printer, but not the ability to input. And color-correction skills are hard to acquire. The average person can end up ruining a file by trying to correct the image.”

Security is always a concern when it comes to digital technology. Giclée is no exception. The process involves computer files, which could include initial images from scans, saved versions of an image file as it’s touched up and color corrected, an image file used for soft-proofing on screen, or a print-ready file that may reside on a RIP server. And with all the files comes the burden of management. How can a giclée studio prove that an edition is truly limited, or that an employee won’t switch on the inkjet after the shop closes? It can’t. The print-on-demand digital business model negates the idea of a true limited edition.

Most giclée studios would argue that retaining at least the file used for printing is a favor to the artist. In any case, part of the process of creating daily system backups includes archiving the image files. And most studios take the precaution of creating redundant backups–multiple copies of each image file–and storing each copy in a separate location. In the end, as Cone puts it, “There’s nothing but honor. There’s really no way to stop an unscrupulous printer.”

Duganne presents a legal disclaimer to artists who are interested in working with his studio. The document essentially returns copyright ownership to the artist. He explains that current copyright law contains a loophole that gives the printer copyright control of any reproduction. “We indicate total ownership of the image by the artist,” he says. “What we create as the printing file is proprietary–the artist doesn’t even get that. But the artist is the only one who has access to it.”

Protection doesn’t stop with computer files and copyrights. What about the prints? Many studios turn to screen printing when finishing their giclées. Duganne says his studio uses screen printing to apply a protective coating that is absorbed by the final prints. And that raises questions about longevity.

Permanence

The permanence of serigraphs and giclées is determined by the substrates and the inks from which they’re produced, and the protective measures and storage methods used with them. Duganne says that comparing the two techniques isn’t practical because serigraphy works with dense, pigmented inks and binders that are layered onto the substrate. He explains that piezo-based output devices put down a very thin ink coating, which makes archivability a problem. “Even if you’re using pigments, the coating you need to put on the paper to receive inks from a piezo printer is so highly engineered that it interferes with the pigments,” he says.

Cone sees it differently. He claims that inkjet inks–particularly pure-pigment varieties–have been thoroughly tested to ensure dependable permanence. “Serigraphy didn’t come under the very tough scrutiny that inkjet did. As a result, inkjet inks have really progressed,” he says.

Herta Headrick, founder of Torrance, CA-based Kolibri Art Studios, insists that serigraphic inks offer the most permanence. “You can walk on [the prints] or leave them outside,” she says. Kolibri uses water-based screen inks that Headrick claims are as durable as conventional solvent varieties.

Printing methods, ink choice, and protective measures are all useless if the print is mishandled, stored improperly, or displayed in harsh environments. R. Mac Holbert, co-founder of Nash Editions, Manhattan Beach, CA, explains that most museums have policies that preclude them from displaying art prints for more than three or four months at a time. “Most fine art and fine-art photography will spend its time in a drawer in dark storage,” he says. So in some cases, the issue of permanence may not have much bearing on an artist’s or publisher’s selection of a printing method.

Coexistence

Is it possible for serigraphy and giclée to get along? Dodge says coexistence is possible because the techniques are so dissimilar. Headrick’s studio has capitalized on this dissimilarity and relies on both serigraphy and giclée. She attributes Kolibri’s ongoing profitability to the addition of digital-imaging technology. “I had a lot of artists come in and ask for serigraphs. When they heard the price, they couldn’t do it,” she says. “That’s the reason we went into digital–to provide services to artists who didn’t have big publishers behind them to produce art.”

But branching out also opened Headrick’s eyes to certain realities of the art market. “Most digital printers, in my estimation, are no better than Kinko’s,” she says, “and that’s sad because it has made the serigraphy market suffer a lot. Anybody can do a giclée. The public doesn’t know what a good giclée or bad giclée is.”

Headrick also notes that having the capabilities to do serigraphy and giclée has attracted new business from mixed-media artists. “Most of the projects from my biggest customers in Japan are digital prints with screen-printed spot colors or special-effects colors,” she says, “and that’s helped keep me in business.”

Headrick’s strategy could be interpreted as a sign that serigraphy is on the endangered list. But Dodge says that demand is swinging back to serigraphy, and studios that maintained their integrity are doing very well. She believes that the art market’s methods of promoting giclées are often misunderstood by the public and are sometimes outright misleading, which will contribute to serigraphy’s longevity. “People don’t know what they’re buying,” she explains. “If you see an advertisement for a print and it doesn’t tell you what the print is, you’re guaranteed it’s a giclée. Some publishers try to pass off giclées as actual serigraphs. They have no ethics.”

Cone believes there will come a time when serigraphy will no longer be viable for fine-art reproduction. But he credits serigraphy studios with having valuable experience in working with artists–a skill set he finds is sometimes lacking in the digital arena. “[Serigraphers] know how to communicate, understand, and interpret,” he explains. “They may not have the digital skills, but anyone can acquire those. Communication with the artists is more difficult.”

Looks good on paper

Permanence, vibrancy, accuracy, texture, range of color, and other factors are all selling points fine-art ateliers use to attract artists to their reproduction techniques. Serigraphers will argue that their techniques capture the best of these aspects, but you can bet the giclée studios will tell a similar story. Cost is always a factor, but what really matters is how the final print looks. Artists will ultimately make that determination, and if they’re lucky, fine-art customers will agree with their assessments.

SPONSORED VIDEO

Let’s Talk About It

Creating a More Diverse and Inclusive Screen Printing Industry

LET’S TALK About It: Part 3 discusses how four screen printers have employed people with disabilities, why you should consider doing the same, the resources that are available, and more. Watch the live webinar, held August 16, moderated by Adrienne Palmer, editor-in-chief, Screen Printing magazine, with panelists Ali Banholzer, Amber Massey, Ryan Moor, and Jed Seifert. The multi-part series is hosted exclusively by ROQ.US and U.N.I.T.E Together. Let’s Talk About It: Part 1 focused on Black, female screen printers and can be watched here; Part 2 focused on the LGBTQ+ community and can be watched here.

You may like

Advertisement

Inkcups Announces New CEO and Leadership Restructure

Hope Harbor to Receive Donation from BlueCotton’s 2024 Mary Ruth King Award Recipient

Livin’ the High Life

Advertisement

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Screen Printing magazine's news bulletin.

Advertisement

Most Popular

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Case Studies1 month ago

Case Studies1 month agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns2 weeks ago

Columns2 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?