Inks & Coatings

Published

16 years agoon

The discussion of white ink always ranks among the most passionate conversations in which garment screen printers engage. Maybe it’s because no one is ever completely happy with the white inks they use. Or maybe misunderstandings about the proper uses of the various white inks are to blame. Add to those possibilities the notions that few garment printers base their ink decisions on logic and that the ink companies themselves are not always as clear as they could be on the proper use of their white inks.

The discussion of white ink always ranks among the most passionate conversations in which garment screen printers engage. Maybe it’s because no one is ever completely happy with the white inks they use. Or maybe misunderstandings about the proper uses of the various white inks are to blame. Add to those possibilities the notions that few garment printers base their ink decisions on logic and that the ink companies themselves are not always as clear as they could be on the proper use of their white inks. Perhaps printers’ obsession with white inks is rooted in their willingness to try new white inks more than any other new products—and, as a result, spend a disproportionately large amount of their ink budgets on white ink.

I talk about white inks to people almost every day. The one thing that I have learned is we inevitably reach a stopping point in the conversation because two printers can never totally agree on the subject. I told several people in the industry that I was going to write an article about white plastisol. They all looked at me like I was crazy. The overwhelming sentiment was that there was no way to make everyone happy with an article on the subject. I actually knew that before I offered to write this article, and I accept that not everyone will be happy. In fact, before I even start, I estimate that 25% of you will think this is a great article, 50% will find it informative, and the other 25% will decide that I don’t know anything about white ink!

One thing I know for sure is that white inks come in a dizzying array of formulations. Ink companies constantly try to hit on a formulation that will make the greatest number of printers happy—that is, until the competition comes out with its newest ink and steals away market share. Additionally, printers frequently misuse white ink—a low-bleed on a cotton fabric, for example. Screen printers can avoid this issue by familiarizing themselves with the variety of white inks for garments.

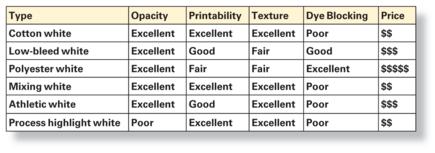

Types of white plastisol

I categorize white plastisol inks into six basic types. You may argue the validity of having more or less, but by my count, the categories are cotton opaque, low-bleed opaque, poly opaque, mixing, athletic opaque, and process highlight. Each has its own properties and cost (Table 1). Even though five of the six ink types I’ve listed are classified as opaque, that does not mean they necessarily cover properly in one pass. Rather, they are as opaque as they can be while still retaining their printability. I’ve left out specialty whites, such as high density or suede, as they really are different in application. The white inks that I’m talking about are the ones used for underbasing and highlighting.

Cotton whites These should be the most common whites used by most printers. They are designed to be used on cotton, nylon, and any other non-dye-sublimating fabrics (i.e., polyester or polyester/cotton blends). They have an excellent after-print finish, they take overprinting well, and they do not have any tendency to ghost (Figure 1).

Few printers actually use a cotton white. Instead, most use a low-bleed white for all fabrics. Their reasoning is usually that it’s easier to use one white for everything. While I understand the logic, the downside is that they are using a more expensive ink—and one that also gives a rougher finish and may result in fabric ghosting (more on ghosting later).

Low-bleed whites These inks are designed for use on polyester/cotton blends. They contain chemicals that are designed to block the dye that may be released from polyester fabrics and prevent the color from tinting the image. Most of these inks do very well in accomplishing this mission. Some do it better than others, either because of the amount of blocking agents in the ink or the ability to flash extremely fast, which minimizes the amount of flash necessary and thereby reduces the amount of dye that may be released.

Unfortunately, these inks have become the standard in our industry. Low-bleed inks, in addition to the attributes mentioned above, contain chemicals that cause an expansion of the ink film, which results in more texture than in cotton whites. This rougher finish can also lead to craters, where the white underlay may show through the finished print after the finished print is cured in a hot dryer (Figure 2).

The other negative—one that does not happen often, but will always happen when you least want it to—is ghosting. Ghosting is a phenomenon in which low-bleed chemicals out-gas from the print and attack the dyes in the fabric in contact with the print. This usually occurs when the fabric is stacked hot and allowed to sit for an extended period, like overnight, and the out-gassing chemicals bleach the dye right out of the cotton fabric above.

You will never see ghosting on standard colors such as black and red. You will never see it on poly-blend fabrics. Where it will occur is on fashion-color fabrics and pastels, where the dyes are not as stable. I’ve most recently seen the effect on pink, sage, pale yellow, and very light tan fabrics.

Polyester whites Polyester low-bleed whites are basically your regular, low-bleed white inks on steroids. The chemicals that help to block the polyester dyes are maximized and are limited only by the need to keep the ink printable. Most printers are a little shocked by the ink’s consistency and viscosity when using it for the first time. Poly whites are the most expensive white inks because of all the added ingredients. They are only needed on 100%-polyester fabrics and are really too strong and too expensive to use as a regular, low-bleed white ink on blended fabrics.

These inks have excellent opacity, but they still require a print-flash-print technique for proper white-only coverage. Also, please note that the manufacturers call them low-bleed, not no-bleed. Improper technique or bad fabric can still defeat these inks.

Mixing whites Mixing whites are opaque white inks that are formulated specifically to be used for mixing colors. The ink manufacturers usually make them as part of a Pantone color-simulation system. Mixing whites are not usually as optically brightened as whites designed to be used on their own. If you look at a mixing white print next to a good opaque cotton white, the cotton will more than likely look more vibrant. Ink manufacturers use brighteners in much the same way as the paper industry does to make the ink more appealing to the eye. The human eye looks at blue shaded whites as being brighter. Unfor-tunately, this blue shading can play havoc with ink mixing, as it may shift colors too much. A less bright white works better as a mixing ink.

Mixing whites can also be used as standalone inks. I know several printers who use their mixing white as their underbase ink. They feel that the ink flashes better and has better after-flash-tack characteristics than other whites. They then use a cotton white or low-bleed white as their highlight white to give them the desired brightness. Mixing whites are just about always cotton whites. There are some mixing systems that supply a low-bleed mixing white, but the use of low-bleed whites in mixing systems is not common.

Athletic whites Athletic whites are like cotton whites, except that they have added ingredients to give the ink extra stretch and gloss. They are designed to be used on athletic jerseys where flexibility, abrasion resistance, and opacity are all important (Figure 3). They can be used on other garments, such as T-shirts, but their expense is usually not justifiable. Athletic prints are increasingly being produced on 100%-polyester jerseys. These fabrics require the use of the polyester ink mentioned earlier. Standard athletic ink will not block polyester dye.

Process highlight whites Process highlight white inks impart the lowest level of opacity of any white ink. They are not made to be anything but a complement to process-color inks. Part of this lack of opacity comes from the fact that they are designed to be printed through the high mesh counts used in process-color printing.

Why is no one ever happy?

White inks are not the easiest inks to use. They’re thick, they can be sticky, and they can vary in their usability depending upon shop temperature, platen temperature, fabric, and a host of other little bothersome variables. I have used white inks that I loved one day and hated the next. I don’t think that is an unusual sentiment. So when the ink manufacturer or distributor tells you about a great new white, you jump. At trade shows, fully half the conversations in the ink booths pertain to white ink. Ink companies could have mind-blowing displays of all their new specialty inks and printers would still walk right past them and ask about new whites in hope of avoiding frustrations on press.

Many factors contribute to the problems associated with white inks. Aging is a big one. Ink can change in viscosity and printability as it gets older. This situation is especially common with white inks, which have a tendency to get thicker as they get older. The easiest solution to this particular problem is to never buy too much white ink at one time. Stick to 30-day supplies as a maximum, and make sure to rotate your inventory so buckets never get old.

Another common issue is using the wrong ink in a given application. I think this is the leading cause of dissatisfaction with a white ink. The main problem, as explained earlier, is using low-bleed whites for everything. The rough prints they produce look like they are out of focus. They lack the crispness of a properly registered and printed cotton white, for example. When low-bleed whites are heated up, the gas that becomes trapped expands and may actually pop. If the expansion and pop happen in the dryer, they will show as a hole with white underneath in the finished print.

Emotional response, not logic, usually dictates selection of white ink. Sure, price is a logical factor, but even if the price is right, most answers I hear for why someone likes a particular white revolve around emotion. Here are a few examples:

• I like this white because my staff complains about it less than any other we have tried.

• I like this white because I have always used it.

• I like this white because it is brighter than any other I have tried.

• I like this white ink because it is cream- ier and easier to print.

Now the last one may actually be valid. However, it may be that the other ink the printer tried was an older batch and may have just aged a little.

As far as brightness is concerned, I have not seen a white ink in the last ten years that was not bright enough to satisfy print customers. The only people who constantly look for brighter whites are printers themselves. That begs the question, are you going to print the two whites side-by-side and have the customer select? If you see them by themselves, they look fine. The only time one may look duller than the other is when they are put next to each other. I haven’t seen too many shirts sold that way.

And speaking of selling, I do admit that ink companies are partially to blame for garment printers’ frustrations. Many of their sales reps do not know as much as they should about the inks that they sell. And even those who do understand the inks will sometimes go with the flow and not upset the customer. Instead, these eager salespeople should try to help by convincing clients that the inks they think they should buy simply are not the right ones. The low-bleed vs. cotton white dilemma is very much an issue that cannot be blamed solely on the garment screen printer.

Modification and curing

Printers care about white ink because they spend so much money on it. With many shops, it represents 40% or more of all the money they spend on ink. You have to care about it when it represents that much money. And in this modern world, with ink prices going up rapidly thanks to petroleum, printers will care even more. Why, then, do printers insist on putting even more money into their white inks by making improper modifications to them?

White inks are, without a doubt, the most shop-modified inks of all. Using additives to change the way your inks behave can be a sensible move. For example, when a bucket of white sits a round for several months—because the printer was using the right ink and not the low-bleed stuff for everything—it gets too thick. Well, a small amount of curable reducer brings the ink back to a very useable viscosity without any detrimental effect on the bleed resistance. However, adding soft-hand base would not be such a good idea. You’d have to dump in way too much to make a difference. And even though soft-hand base would improve the viscosity, it would do so at the expense of opacity and bleed resistance. Soft-hand extender base would be proper to use in a highlight white ink to be printed onto a light fabric. In this situation, opacity is not as important and you can save money and improve printability by adding the soft-hand base.

White ink also is the most commonly flashed ink. As such the flash characteristics of any white ink become a crucial factor in deciding whether or not to use it. In general, most printers flash too much. They either flash a print for too long, too hot, or both. The results can be catastrophic. An over-flashed underbase is actually a cured underbase. Plastisol does not stick well to cured plastisol. If the underbase is over-flashed, the inks printed on top of it may actually fall right off the first time the shirt is washed.

The phenomenon in play here is called intercoat adhesion. The object of flashing is to gel the ink, not cure it. When the ink is gelled, subsequent colors will bond properly. When flashed well beyond gelling, the ink is cured and the top colors fall right off. It is as if you were printing plastisol on a vinyl notebook.

A print is properly flashed when the ink is just past the point where any will transfer to your hand or to another garment. Most printers start out in the morning at the proper time and temperature. The problem is that as the platens warm up, the shop neglects to turn the flashes down to compensate. Flashes require constant attention. They are not set-and-forget devices.

Set your sights on whites

A little effort to use the right ink for each application will help save money, time, and improve print quality. Have multiple whites in your shop for different applications. If athletic and process-color printing aren’t part of your services, then you should only have three whites: a cotton white, a low-bleed white, and a mixing white. If you do process-color printing, but not athletic printing, then you only need to add a highlight process white to the three formulations previously mentioned. If your shop does it all, then you can justify stocking all six types of white discussed in this article. So pay more attention to the white inks that you use. Focusing your investments in white ink on the jobs you print will go a long way to keeping your company in the black.

Mike Ukena is a 15-year screen-printing veteran who has owned a textile-printing company and worked in technical services for the SGIA as the director of education. A member of the Academy of Screen Printing Technology, Ukena is a frequent speaker on technical and management topics at industry events. He is currently a technical sales representative for Union Ink Co., Inc.

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Screenprinting Magazine.

Most Popular

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Case Studies1 month ago

Case Studies1 month agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Andy MacDougall1 month ago

Andy MacDougall1 month agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns2 weeks ago

Columns2 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?