Articles

Published

22 years agoon

A good screen printer, competent in screenmaking and all other stages of the process, can produce better results by hand-printing than the most sophisticated automatic machine in the wrong hands. I do not wish to understate the importance of good machinery and well-formulated screen inks, but without a suitable screen, you cannot get a decent screen print.

The same is true in the digital world with inkjet printing, where the screen’s equivalent is the inkjet printhead. The printhead governs the type of ink that can be printed and is one of the prime determinants of resolution and image quality. Yet for many inkjet buyers, the capabilities and limitations of different printhead technologies are grossly misunderstood. This is the main reason why Screen Printing magazine commissioned me to write an article on inkjet printheads–and why I was happy to oblige.

The role of the inkjet printhead

Typically any inkjet printing machine comprises the following components: some type of media/substrate transport mechanism software, usually including a RIP (raster image processor), printer driver software, and design or layout software a front-end and/or on-board processing system–computers that are used to manipulate the above software a print engine, comprising printheads or printhead assemblies and any necessary ink management (temperature, viscosity, consistency, delivery, and filtration) systems

The printhead is inkjet printing’s nearest equivalent to screen-printing mesh. An inkjet printhead is the means by which ink is transferred in a controlled manner to the substrate. Similar to a screen, it limits the viscosity range of the inks that can be reliably printed and restricts the solvents that they can contain. The printhead is also a primary controller of ink-droplet size, and thereby exerts a strong influence on resolution and image quality, although the final arbiters here are the software (RIP and printer driver) often combined with the media or substrate, which affects ink capture and spread.

Sometimes, when a large head assembly is required to support high print speed or greater imaging width, several printheads may be built into a larger integrated head structure. This can be costly, as the engineering, electronics, and software required to get all these heads to fire reliably and predictably (i.e., interlace their output) must be implemented by highly skilled system integrators. Frequently, these integrators are independent from the printhead or machine manufacturer.

Resolution and image quality

Digital-image quality is often–but very inadequately–defined by dpi (dots/droplets per inch). One might also assume that the resolution of a printer (in dpi) is equal to the resolution in dpi of the printhead, but this assumption is not reliable. Often, printheads are angled (relative to substrate direction or the direction of head travel), which enables higher-resolution printing, or, at any rate, more droplets per inch. Alternately, the heads may be double-stacked; for example, two 180-dpi heads may be configured in tandem, enabling 360-dpi printing resolution.

Unfortunately, the term dpi tells us nothing about droplet size. It tells us how many droplets we print every inch, but on a microscopic scale, are these dots basketball, baseball, or golf-ball size? Obviously the size of the ink droplets has a big effect on true resolution and image quality.

Today, droplet sizes range from less than 5 picoliters (pl = a millionth of a millionth of a liter) with the finest thermal and piezo printheads up to more than 100 pl on some piezo models and much higher on specialty printheads for marking and coding applications. To complicate matters, piezo printheads are now available from the likes of Epson, Brother, and Xaar that support multiple droplet sizes, making it possible to enhance “apparent” resolution way above the dpi of the printhead.

Basic types of inkjet heads

Inkjet printing is not so much one process as a family of processes–in that way, it is akin to screen printing with its many variants. I could get complicated here and talk about all the wondrous and marvellous inkjet printhead technologies that are available today and their applications. However, in an article focusing on inkjet for wide-format graphics, there is no need to do this.

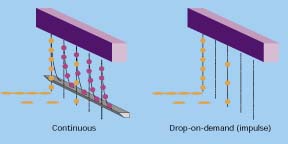

The illustration on the left shows the fundamental difference between two major classes of inkjet heads: continuous inkjet (CIJ) and impulse or drop-on-demand (DOD). Most CIJ systems have been designed and manufactured for marking, coding, and packaging applications by companies such as Trident, Domino, Imaje, Marconi (Videojet), Willett, and Markem. Several printheads and print engines have been developed for these demanding applications, but generally all produce very large drop-let sizes.

In the future, such heads may become important in certain textile applications, but CIJ heads are no longer very relevant for the bulk of graphics applications. I say this with due respect to the fine art and giclée printers of Iris Graphics and Ixia, and to NUR, whose Wideboard and Blueboard ranges boast CIJ heads. Yet even the mainstays of NUR’s current product range, the Salsa and Fresco printer lines, are based on piezo DOD technology.

The main subject of this article will be DOD technology, which uses a discrete electrical signal (or waveform) to fire individual ink drops from each nozzle of every printhead. Three printhead types comprise the DOD inkjet family: electrostatic, thermal, and piezoelectric.

Electrostatic DOD inkjet has absolutely nothing to do with the electrostatic printers marketed past and present by Xerox, Gretag (Rastergraphics), 3M, and Phoenix Graphics. Furthermore, the process is not used for wide-format graphics applications. One down, two to go.

Thermal DOD inkjet

Thermal inkjet (TIJ) heads are mass-produced for color inkjet printers in home and office environments, often called the SOHO (small office and home office) market. Subsequently, such heads have been built into machines for CAD, drafting, mapping, and wide-format graphics by companies such as Hewlett Packard (HP), MacDermid ColorSpan (formerly LaserMaster), Encad, Canon, and others, using TIJ heads from HP, Lexmark, and Canon.

Probably in excess of 90% of all inkjet printheads manufactured today are of the thermal type. TIJ has proven itself a versatile and reliable technology for the home and office markets and certain wide-format sectors, successfully competing with the highest resolution piezo technologies, as shown by HP’s global leadership of the SOHO inkjet and CAD markets, and Canon’s number three position.

I am going to keep the discussion of this technology brief, even though it has a very strong market presence and good future in certain applications. Why the brief analysis? Because thermal heads today, and probably for the foreseeable future, are limited to printing low-viscosity water-based inks. They also have a finite life that is generally shorter than equivalent piezo heads.

Most importantly, the main drivers for TIJ technology today are the home/ office and photoreproduction markets, which share the goals of ultra-high resolution, small droplet size, and photorealism. Few screen shops want to focus their printing solely on jobs that require 450 thread/in. mesh and water-based inks, so why should a screen-printer using inkjet technology want microfine droplets and water-based inks for every application? Not surprisingly, they don’t!

Piezo DOD inkjet

To be fair, most piezo DOD heads are also manufactured for the SOHO market, with Epson the global leader in this technology sector. Once again, the product performance and reliability are very strong with these piezo heads, and they have been built into several wide-format printers, notably models from Roland, Mimaki, Mutoh, Epson’s own wide-format range, and the Gretag Bellise.

Piezo printheads typically last longer than thermal heads, although fewer are made, and they are more ex-pensive to manufacture. In fact, after battling for some 15 years, HP, with its development of water-based thermal inkjet, and Epson, with its parallel development of water-based piezo inkjet have succeeded in reaching a draw. Both technologies can now print droplet sizes well under 5 pl and both are reliable and consistent. However, I would suggest that photorealism and minute ink droplets is not where the bulk of the wide-format market needs or wants to go.

So, at one extreme, we have the huge ink droplets produced by most CIJ and piezo CIJ systems. At the other, we have the minute droplets produced by photorealistic home and office inkjets based on thermal DOD or piezo DOD heads. In between is the range of resolution requirements and ink deposits needed for most wide-format applications. Such applications also require direct printing onto raw and uncoated substrates, rather than high-cost speciality media, which implies a need for something beyond water-based inks–namely solvent-based and UV-curable inks.

Evidence thus far suggests that these needs today can be met by only one branch of the inkjet family: piezo DOD heads. As the illustration below crudely shows, many different patented architectures exist for piezo heads, including face shooters, piston structures, or moving wall structures.

Not all piezo heads are created equal. Perhaps this is an obvious statement, but I must explain further. Among the large portfolio of piezo head manufacturers and architectures, heads are available that can print large droplets, medium droplets, small droplets, or even a range of different-sized droplets. Some can print inks containing pigments or dyes. Some use inks that are based on water, solvent, or oil. Some are even designed for UV-curable, hot-melt, or hybrid ink systems. Available piezo DOD systems include those that can print fast and those that print less quickly. But virtually no piezo printhead can do every one of these things.

What all this means is that the machine builder or OEM must select the best head for the target application. This selection process requires skill and a detailed knowledge of the target market and application, something that not all manufacturers had in the past–and a few still don’t.

Another important issue is that piezo heads just love to print. They do not like standing idle, which can lead to blockages and other problems. This explains why some of the earliest industrial-speed wide-format machines, which built many heads into wide arrays and tended to fire less ink through each head, often suffered from reliability problems. The machine builder, the ink formulator, the software designer, and finally, the operator and working environment, all have a strong influence on the way a particular printhead performs. The same printhead will often perform differently in different machines.

I have too little space to describe all of the piezo printhead options in detail, so will concentrate on two manufacturers who are having the strongest influence today on the industrial speed machines for the wide-format graphics sector–and one more who may in the future. I send apologies to Hitachi Koki (formerly Dataproducts), IJT/OTT, Picojet, and the many Xaar licensees whom I have not mentioned.

Spectra, Xaar, and Aprion Technologies

Spectra

Founded in 1984 in Hanover, NH, Spectra’s (www.spectra-inc.com) original goal was to produce inkjet heads for the imminent and growing office market. However, the repackaging of thermal inkjet as a low-cost process by HP eliminated office-based opportunities for Spectra and other young printhead companies. Instead, Spectra refocused on industrial applications, a market where it has been quite successful.

Spectra heads are winning a reputation as being among the most robust and reliable in the industry for solvent-based inks, and they are now found in the latest machines from Vutek, Heidelberg, L&P Digital, Olec, and Durst. Spectra’s primary ink partners include SunJet (formerly Coates Electrographics), Sericol Imaging, and Flint Ink, although they have working relationships with many other ink manufacturers.

One of Spectra’s latest heads, the Nova-Q aqueous printhead, is capable of printing water-based, solvent-based, or UV-curable inks. This head is a modification of Spectra’s Nova 256/80 head, as found in the Vutek 2360 and 3360 machines. It features four, 64-nozzle piezo modules, giving a total of 256 jets, and claims a lifetime rated at 25 billion droplets per nozzle, which equates to about 500 litres of ink per nozzle.

Xaar

Based in Cambridge UK, Xaar (www.xaar .co.uk) is a spin-off company from the consultancy group Cambridge Consultants. An early use for its “flexing sidewall” piezo technology was a postage-printing system for Pitney Bowes, and from such beginnings, Xaar developed into a serious development and licensing group for piezo inkjet head technology.

One of Xaar’s earliest licensees was IBM, which, in Sweden, started manufacturing piezo heads aimed at the global corporate and office markets. When aggressive and agile PC manufacturers wrestled control and marketshare from IBM, economic realities forced Big Blue to spin-off marginal business activities, such as Lexmark, its thermal inkjet head and printer company, and also its Swedish piezo operation, which became Modular Ink Technology (MIT).

MIT heads first came to the attention of the graphics industry via the Rastergraphics PiezoPrint 5000 and equivalent Olympus/Xerox products. In 1999, Xaar was floated, making a handsome profit for its original investors and generating a cash surplus that enabled it to purchase MIT, its leading licensee at the time. MIT subsequently became XaarJet AB, Xaar’s Swedish plant.

Xaar’s position appears unique in the industry. On one hand, it is now a sizeable manufacturer of piezo heads; on the other, it licenses manufacturing technology to many companies, including Brother, SII (Seiko Instruments), Konica, and Toshiba. Xaar representatives state that there is no problem with this ap-proach, in that the company’s own markets do not conflict with those of its licensees. That may have been true in the past, but there is growing evidence that some licensee-manufactured heads are now becoming available in the open market and may be built into new wide-format machines. Xaar faces the future prospect that it could find itself competing with its own licensees for certain applications and vertical market sectors.

Xaar’s piezo heads include the XJ128 (former MIT head) as used in the Gretag Arizona and Scitex Grandjet range, and the XJ500 range now appearing in emerging flatbed inkjets, such as the Zünd UVjet Sheetmaster and Inca Eagle 44, as well as other new models. The mainstream products work with oil-based, UV-curable, and certain solvent-based inks. Until recently, Xaar did not manufacture a head for printing water-based inks, although the recent launch of the XJ126 should address this issue. As yet, we are unaware of any systems using this printhead.

The SII printhead from Seiko Instruments, one of Xaar’s licensees, is a 510-nozzle head capable of 180-dpi natural resolution over a 3-in. print swathe at 12.8 kHz drop frequency. This head can produce droplets of 12-pl or 40-pl volume.

Aprion Technologies

A spin-off from Scitex Corporation, Aprion Technologies (www.aprion.com) was an Israeli company founded in September 1999 with $33 million in venture capital, including an 18% stake by Scitex itself. Aside from Scitex’s initial financial support, much of Aprion’s basic technology and many personnel came from Scitex.

Aprion recently moved to a new purpose-built 6,000-sq-m manufacturing facility in Poleg Netanya, near Tel Aviv. While current printhead production is reported as “a few hundred heads per month,” the company predicts a capacity to manufacture 20,000 heads per annum.

The heart of Aprion’s printers is a piezo head technology called “MAGIC,” an acronym for Multiple Array Graphic Inkjet Color. This refers to its wide-array heads with very thin cross section, which are capable of fast printing at 600 dpi.

The design of Aprion head technology appears well thought through . The piezo transducers are separated from the ink chambers by a thin steel diaphragm, which means there is no direct electrical or thermal interaction between the piezo crystals and the ink, permitting broad formulation possibilities. Ink is fed into the respective chambers via a porous metal inking layer, rather than any single channel.

Aprion’s initial trials indicate that this should be a very robust solution, because if any dust, particulates, or pigment agglomerates enter and cause a blockage in the porous ink carrier, many alternative feed pathways remain available. Perhaps more importantly, it may promote faster refilling, allowing the head to be fired more frequently and leading to faster printing speeds.

While few machines featuring Aprion heads have yet been sold, this situation could quickly change. Aprion heads are built into machines such as the DPS 65 printer for textile and wallpaper decoration, distributed exclusively by Digital Printing Systems, New York, NY. Other imminent products include flatbed printers targeted at the rigid packaging industry, such as the Belcom 2000 from Belcom, Chicago, IL, and a similar machine from Lasercomb in France.

With Scitex’s financial involvement, it is little surprise to learn that the new Scitex ENjet, a 150-sq-m/hr, six-color digital flatbed press, is also based upon Aprion technology and water-based inks. During a recent visit to Aprion, I was surprised by the resilience and adhesion that the water-based inks exhibited.

We now wait with interest to see just how far Aprion technology can go in respect to flexibility of ink formulation–will it be able to handle solvent-based, UV-curable, or high-viscosity inks? Aprion believes yes, although the company’s main focus today is water-based formulations, which it believes will satisfy most needs while offering an environmentally benign chemistry.

We must, however, exercise caution in our assessment of Aprion’s technology, since it has yet to be tested in serious production environments. Also, the journey from prototype inkjet heads to cost-effective high-volume head production can be torrid and prolonged. Nevertheless, Aprion’s approach is novel, and they may well achieve something revolutionary.

Where next?

In a recent Information Management Institute conference in Scottsdale, AZ consultant Mike Willis remarked that “the inkjet head manufacturers are becoming promiscuous.” Only a few years ago, the main head manufacturers exercised a strong control over the ink supply used with their printheads and worked with a very limited number of ink manufacturers. Now that situation is changing.

Every month one reads of “new strategic partnerships” or “technology licensing arrangements,” which illustrate the inkjet industry’s increasing openness and its acceptance of the commercial power of some traditional ink providers who have more recently entered the inkjet market. The head manufacturers still need some ink revenue to finance their business and technical development, but that revenue is being siphoned through more complex commercial relationships.

We might infer that in light of changing market power, there may be too many companies involved in inkjet-head development or manufacturing to be sustained by the industry. That could be an erroneous conclusion for two reasons.

Firstly, inkjet printing has tickled at the sides of the screen-printing industry and is now at last beginning to impact upon screen markets. But until recently –perhaps not until after DRUPA 2000–most major machine manufacturers in the offset and flexo sectors did not understand the full potential of inkjet. These companies are not struggling for survival; they are sizeable industry players that might come to regard inkjet printhead technology as a core competence to be acquired or even controlled, and they have the resources to do so. If such vertical consolidation occurs, there might not be enough inkjet head manufacturers to go around.

The second issue is focus. In the past, almost every inkjet-head company (and most OEM’s and machine manufacturers) focused on one ubiquitous substrate–paper. Ironically paper is, in general, the cheapest printing substrate on planet Earth and one of the lightest and thinnest. This means that it is the substrate that pays the lowest returns in respect to reduced wastage, inventory reduction, and lower transport costs. Change the scenario to glass, acrylic, metal, textured or hard-coated plastics, and the picture rapidly changes. Wasting 50 sq yards of glass carries the same expense as wasting 1000 sq yards of paper. The potential for inkjet printing to permit cost savings over traditional technologies and workflows on non-paper substrates puts a value on these applications that is much larger than the size these niche industries would suggest.

To go back to the screen mesh analogy, we now have three or four major grades of inkjet printhead, enabling three or four groups of ink deposit/coverage and resolution. To take on all opportunities within the screen/offset/flexo/gravure markets, we need a wider range of heads with different drop sizes, ink compatibilities, and production rates.

We also need new heads with even higher reliability and the flexibility to support a wider range of ink formulations. The inkjet-head developers have made a start, but they still have a long way to go.

Each time a leading head manufacturer makes a new breakthrough in performance, we may expect, a year or so later, to see yet another generation of new inkjet machines for existing and exciting new applications. If you are a screen printer or screen-print supplier, the small bite inkjet is making into your markets can only get bigger. For flexo packaging printers and offset printers, the future may take a little longer to arrive, but keep a watch on the new flatbed presses linked to new business models. Inkjet will not revolutionize the printing industry tomorrow, but we at Web Consulting believe that one day it will, in value terms, be the world’s most powerful printing technology.

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Screenprinting Magazine.

Most Popular

-

Case Studies2 months ago

Case Studies2 months agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns3 weeks ago

Columns3 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?