Prepress & Screen Making

Published

17 years agoon

Very few screen shops can truthfully claim that everything runs right all of the time. In reality, managers constantly struggle to maintain order and control. As our image requirements continue to increase, it becomes more and more important to work from a standardized, documented position. When quality becomes erratic and our screens become unpredictable, the red flag goes up and we begin the hunt for causes. This is an expensive and time-consuming affair. This month, I would like to share some experiences and observations about process control along with remedies to make your life easier.

A root cause of the majority of the variations I see in the way tasks are performed is lack of established and documented procedures. Most of the companies in our industry grew up by the seat of their pants. Experienced printers verbally pass on what they know to the new guy. The new guy soon becomes the experienced guy and he passes on his knowledge the same way. I call this tribal knowledge because it is passed on by word-of-mouth from one elder to the young bucks coming up.

While this may have been the way in primitive societies, we live in a technologically driven digital era. Our work is too technical and too precise to rely on the verbal ways of the past. Besides, people forget and do things differently. Processes morph over time until we’re no longer able to deliver on demand.

To make matters worse, people have a funny way of changing things up when they get bored. When a screenmaker coats hundreds of screens a week, the same way, sooner or later he’s going to try something different. It may be ever so slightly different, like coating two-over-three instead of three-over-two. Or deciding that two-over-two makes more sense than three-over-two. This is a small change that may or may not have a visible effect. But that isn’t the point. The problem is the screen-coating procedure has moved one step away from what we absolutely know works for us.

It’s the next small step away, followed by the next step, that causes the real grief. By the time real problems show up on press, and the manager steps in, the damage has been done. We’ve all experienced periods where everything seems to stop working. We can’t get a good result to save our lives. When we go in to investigate, we find so many changes from the established practice that reestablishing our known values becomes a huge undertaking.

Here’s a perfect example. A screenroom technician opens up the exposure unit to replace the bulb. No problem. He’s done it many times. In the process of changing the bulb, he notices there’s a lot of dust building up on the leads and the transformer connections. After vacuuming everything out, he notices that the power is set to 240 V on the transformer. Knowing the line voltage is 208V, and that there’s a setting for this voltage, he casually flips the switch to the correct line voltage. No problem.

After buttoning up the unit and getting back into production, he notices his screens aren’t washing out the way they normally do. He narrows it down to an exposure problem, but the cause remains a mystery. The focus is on the new bulb, so they call the supplier and order a new replacement, overnight air. The screenmaker is half a day behind, and now he has to wait until 10:30 the next morning to get the bulb and then spend another half an hour putting it in. He gets his first screens off at 11:15, and they’re still bad.

Now it must be bad emulsion. So he mixes new emulsion and coats more screens. Time for lunch. By 1:00 in the afternoon, he’s ready to go after it again. The problems continue, and he also notices much more moiré than usual. By now, the floor is screaming for screens and jobs are getting bumped. More screens have to be reshot. In fact, all the halftone screens seem to be having some kind of problem. He can’t figure it out. He messes around with it for the rest of the day with no solution.

The production supervisor gets called in the first thing next morning because the floor is now behind on the schedule and the work isn’t matching anything the shop has done in the past. It’s a big headache and a mystery. No one can figure out what’s going on. Two more days pass—the problems haven’t gone away. More cost, more time, more lost production.

After a full week of utter and complete frustration, con-fusion, and mystery, the owner of the company asks whether anything unusual has been done. The original screen tech scratches his head and says, innocently, “The only thing I did different was vacuum out the dust, and I changed the transformer voltage to match the line voltage.” That one, simple, innocent, well-intentioned action caused thousands of dollars of wasted screens and tens of thousands of dollars of wasted and delayed production, including the compromised product that did not match previous work.

This is a true story, sad to say, and it’s repeated in some form regular-ly across the country on a daily basis. The solution is process control, training, and documentation. While most shops have some element of this in place, the practice is sadly lacking and almost universally deficient. It doesn’t have to be painful. Something is better than nothing. What follows is a roadmap for your journey. You can be as complete or rough as you like, but regardless, you’ll benefit if you undertake this approach.

Step 1: Map the process

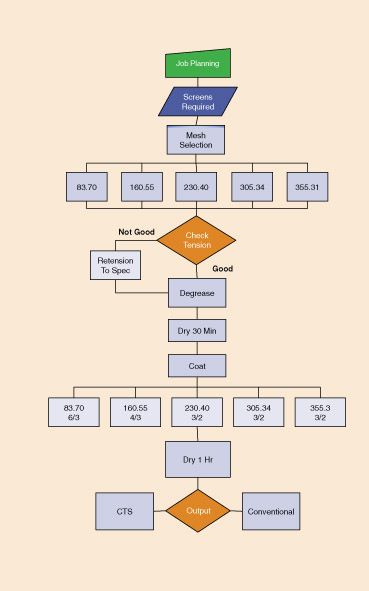

Establish the flow and procedures in the form of a flow chart (Figure 1).

Dozens of inexpensive software programs can do it. Any organization-charting software will allow you to make flow charts. Excellent choices are Microsoft Visio on the PC or The Omni Group’s OmniGraffle Professional (free on the Mac with OS X). Sit down and draw the step-by-step journey through each department. This flow chart establishes the steps and the order you’ll use. It gets everyone thinking. It won’t be perfect at first, but it’ll lead to thoughtful observation and improvement.

Publish the charts and get them into the plant. Put them on the walls where they can be viewed and checked. As you work through day-to-day production, compare what is happening on the floor to what is on the chart. Make changes. Add steps as necessary. Delete redundant or wasteful steps. Work this way for two or three months, revising weekly or biweekly, until you have a good, solid system in place that seems to be working most of the time. There will always be exceptions, and you have to decide whether the exceptions are the result of an invalid process map or due to deviation from the established practice.

Step 2: Develop documentation

Now the work really begins. Each block, each decision, each process step needs to be defined and documented. This is the beginning of your standard operating procedures (SOPs). This is the foundation of any quality organization. It is all about the people knowing what they need to do, how to do it, and when to do it. You are establishing what is expected and the metrics (measurements) that will define your success.

The documentation is your fall back. It allows you to establish a consistent, predictable, and repeatable working environment. It assures that each and every worker will be doing the job the way it is designed, and it narrows the window of variation in the final product.

Start the documentation process at the beginning of the order flow. You’ll have the most benefit from first working on the order planning, art, and prepress areas. When everything is right in these steps, the chance of things going wrong on the production floor goes down.

The documentation must be clear and complete. Don’t assume anything. In fact, one of the biggest challenges you will have is leaving basic foundation steps out. This actually has a name, “The Expert Syndrome.” Experts forget the little steps, like how to hold a coating trough, or remembering to let the mixed emulsion sit overnight to allow any air bubbles to escape. These little details need to be included. Be very precise.

And one more thing, make sure to give each iteration or revision its own Version Number. This allows you to keep track of when the information is revised and to make sure everyone is on the same page (no pun intended). Documentation is an ongoing effort, and it’s important for you to be able to see and track the evolution of information development and delivery. You will never be done with this. Change is at the foundation of technology. What you are doing allows you to stay on top of technology change without everyone digging their heels in and fighting every step of the way.

Step 3: Train employees

The final step is an organized training effort. Again, the process map helps you to develop your training plan. You can clearly see the order of information delivery. It’s easy to make PowerPoint slides for each key concept. The details are defined in the documentation. It’s the combination of documentation and process charts that delivers a one-two learning punch. You have written and visual backup to support you.

Training needs to be reinforced to take root. Having the process charts and the bound documentation moves employees forward and gives them confidence. Everyone learns at a different rate and in different ways. That will be the subject of another column, but for now, start down the path by getting a picture of what you’re trying to accomplish and then fill in the blanks. This relatively small investment in time and effort will pay enormous financial and productivity dividends in just a few short weeks.

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Screenprinting Magazine.

Most Popular

-

Case Studies2 months ago

Case Studies2 months agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns3 weeks ago

Columns3 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

News & Trends2 months ago

News & Trends2 months agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?