Inks & Coatings

Published

20 years agoon

One of the most amazing things about plastisol ink is that printers are interested in getting it at a great price, but once they have it, most of them waste a significant amount of it. They use the wrong ink for a particular application. They contaminate the ink by leaving the lid off of the container or using a dirty spatula to mix it. They leave some of the ink on the screen when they are done with a job. Or they modify ink incorrectly, and when it does not work as intended, they park it back on the shelf to slowly become useless.

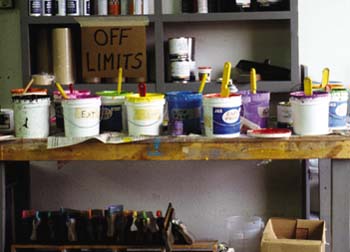

One of the most amazing things about plastisol ink is that printers are interested in getting it at a great price, but once they have it, most of them waste a significant amount of it. They use the wrong ink for a particular application. They contaminate the ink by leaving the lid off of the container or using a dirty spatula to mix it. They leave some of the ink on the screen when they are done with a job. Or they modify ink incorrectly, and when it does not work as intended, they park it back on the shelf to slowly become useless. I am not making these claims from the top of the mountain. I was guilty of these transgressions when I had a printing shop, which is probably why I spot them so quickly whenever I visit garment printers today. My goal here is to help you avoid making the same mistakes by explaining the characteristics of various plastisols, reviewing the criteria to consider when selecting inks and modifiers, and suggesting strategies for handling, organizing, and keeping records about your inks. The color of wasted money Most printers do not waste ink intentionally. The waste usually results from laziness, lack of understanding about the nature of plastisol, and because, as an industry, we have not done a good job of encouraging proper ink-management practices. Plastisol ink itself also is a little guilty because its ease of use makes us forget about its value. Ink represents a very small percentage of the total cost of a printed garment. But if you add up the dollars represented by the ink containers in your ink department, you may be in for a shock. Even a small printing shop using a manual press will easily have $1000-3000 worth of ink on the shelf. A larger printing operation can have up to $20,000 in ink. Unfortunately much of the inventory in shops of all sizes is unidentifiable slop–that is, custom ink mixtures without proper labels. Without a label listing what ingredients a custom ink contains or how much of each ingredient is included, determining if the ink will work for a particular application becomes impossible. Ink management has become even more challenging in the past few years with the introduction of new specialty inks, such as high-density, suede, and gel formulations. New stretch additives and special-effect particles (glitters, shimmers, etc.) have only complicated matters. Today, an unlabeled bucket of red ink could be anything from a multipurpose low-opacity formulation to a high-opacity athletic ink with stretch additive or a high-density ink with a viscosity modifier. Before you can label your inks properly, you need to be aware of the range of ink types and modifiers available and how they behave. More importantly, you need to know how to select among them based on the type of application you’ll be printing. The false nature of plastisols One of the biggest challenges in working with plastisol ink is making sure that the viscosity is correct. Unfortunately, plastisol leads a double life when it comes to viscosity. When it sits for any length of time–even one day–it acquires a "false body" or an increase in viscosity that dissipates when the ink is stirred. Fluids that experience such viscosity drops when agitated are called thixotropic. The thickening of the ink at rest is even more pronounced in cool temperatures or when the inks have naturally high viscosity, even after stirring. If you configure press settings or modify a plastisol before it is stirred, you won’t be pleased with the way the ink performs on press. Most printers are aware of this phenomenon in dealing with white inks, but few realize it is a characteristic of all plastisols. The only ways to address it are to stir the ink before printing or adjust press settings several times during the early stages of the print run as the ink reaches its working viscosity. Spending a little time stirring the ink at the beginning will usually pay the greatest dividends by allowing for a faster production start. Ink opacity Plastisol manufacturers make their inks in a variety of opacities for use on different fabrics and garment colors. Unfortunately, printers often select an ink solely on the basis of its color–even if it is the wrong ink type or has the wrong opacity for the application. Let’s examine different inks according to their opacity levels and explore the proper uses for each. We’ll start with inks that have the lowest opacities and work our way up. Transparent ink To understand transparent ink, consider a pair of sunglasses. They have color, but you can see right through them. A transparent ink has no ability to cover another color without being visibly affected by that color. As a general rule, all process-color inks are transparent. While some ink manufacturers make process-color formulations that are double or triple strength in terms of pigment load, these inks are still transparent. So, why use transparent ink? Because it allows for the most accurate color replication. Transparent inks generally are printed as halftones when you want to expand the gamut of colors in your print without using a lot of ink colors. For instance, yellow and magenta transparent inks printed next to each other or on top of each other as halftone dots will produce a very clean third color–orange. The exact shade of orange can be predicted in advance because of the known values of the transparent inks and their effect on each other at various concentrations. If you do this same test with more opaque inks, you still get an orange color, but it will have a muddy appearance. Also, the final shade will not be as predictable in advance. An important thing to remember about transparent inks is that if they are printed on any substrate color other than white, the printed colors will shift. And if the substrate is too dark, the ink colors may not be visible at all. General-purpose, low- to medium-opacity ink General-purpose inks are the most common class of plastisols. They are offered in the widest range of premixed colors, are easy to use, and can be printed on white and light-colored fabrics without using an underbase. They’ll also cover the substrate without experiencing a color shift. Opaque plastisols Opaque plastisols are thicker and more heavily pigmented than general-purpose inks. They also may contain components referred to as "opacifiers," as well as a certain amount of white pigment (titanium dioxide) to aid opacity. Opaque plastisols are the second most common ink type and the ones most often misused. The error most frequently made with opaque plastisols is that they are chosen for printing on white or light-colored garments, where their heavier pigment load leads to a heavier ink deposit and less intense color than would be possible with a transparent or general-purpose ink. These characteristics create prints with a heavier hand, a decrease in productivity due to excessive ink buildup on screens during printing, and an increase in costs because more ink is used than is needed. Athletic plastisols Athletic plastisols are specially formulated opaque inks for use in printing athletic uniforms. These inks offer high gloss and a cured ink film with the highest abrasion resistance of any plastisol. Specialty plastisols Specialty ink is the catch-all category for any formulation that can not be placed into other categories listed here. Included in this broad range are metallics, glitters, shimmers, suedes, puffs, high densities, and adhesives for flocking and other special effects. White plastisols White inks come in versions that fit within several of the previously mentioned categories, but they are such a major factor in our industry that they deserve separate discussion. White plastisols represent 25-50% of a screen printer’s ink purchases. The inks typically are used for printing underbases on dark shirts, printing highlight whites, and mixing custom colors. Whites are among the most misused inks in our industry. The most common white inks come in high-opacity, low-bleed high-opacity, and mixing-white formulations. In many shops, printers do not differentiate between these types of white ink, which creates very expensive problems and, at the very least, leads to color-matching errors. Technically, a shop should have all three types of white ink for proper production. In an ideal world, high-opacity white is used only for underbasing and highlighting. Low-bleed high-opacity white is used whenever the garment being printed contains polyester. Mixing white is used solely for color-matching applications. Unfortunately, a high percentage of printers use only one white for all of their print jobs, and it’s usually a low-bleed white since this ink type works with fabrics containing polyester. I have asked many printers why they use only one white ink. The most common answer I hear is, "I don’t trust my people to use the right one for each job, so it is easier to just have one." But relying on only low-bleed white for every job causes the following problems: 1. Low-bleed whites cost more, so printers spend more money on ink than they need to. 2. Low-bleed whites tend to have a rougher texture after curing and result in harsher prints. 3. If a printer only uses a low-bleed white, there is a risk of "ghosting" on some shirts. The garments that are most affected are 100% cotton pastels. Ghosting occurs when certain ingredients in low-bleed ink bleach the dye out of the garment above when the pieces are stacked after printing and drying. This problem is rare, but it can occur in certain shop conditions. Besides the three types of whites mentioned previously, shops that do a significant amount of printing onto 100%-polyester athletic wear need to have two additional white inks on hand at all times: an athletic white and a poly white. The athletic whites will satisfy applications that require heavy durable prints (such as football jerseys). Poly whites, the most expensive type of white inks, have the highest level of bleed-blocking ingredients. They are not really needed for use on 50/50 cotton-poly blends, but they are essential for printing on many of the newer all-polyester fabrics, including mesh, dazzle cloth, and canvas. The role of reducers and extenders Reducers and extenders are very important products and should be a standard part of every ink department. If both products aren’t present in your inkroom, your shop isn’t printing garments as efficiently as it could. Reducers and extenders perform very different roles and are not interchangeable. Reducers are most commonly used to lower the viscosity of a plastisol ink, and extenders are used to diminish the color intensity of opaque inks without changing their opacity level. Reducers and extenders are available from many ink manufacturers and in many varieties. Knowing how to use these products correctly can help you avoid drastic problems on press and save you a lot of money through increased productivity and lower ink costs. Reducers The two main components in plastisol reducer are plasticizer and PVC resin. Plasticizer is the liquid component of a plastisol ink. It must be blended in proper balance with PVC resin, the solid component of the ink. When the ink is heated during the drying process, the resin swells and absorbs the plasticizer as it cures into a flexible film. If the components are not equally balanced, you will not get a fully cured plastic film, and the first time the fabric is washed, you’ll lose much of the ink. Several types of reducers are available. I highly recommend that you use only a curable reducer, sometimes also referred to as a detackifier or simply a reducer. You can determine if any reducer in your ink department is curable by observing its color. If it appears milky white or cream colored, it is curable. If it is clear, remove it right away. A clear reducer is not a balanced reducer. It is mainly pure plasticizer, and if too much of it is added to an ink, you may experience very significant curing problems. Curable reducers are balanced reducers. They contain resin and plasticizer, so even if you pour the reducer into the ink without accurately measuring the amount, the ink will still cure. Extenders Extenders are a little more complicated. They basically are unpigmented ink. Most ink systems are supported with one or two different extender bases. An opaque ink system usually will have both an opaque extender base and a soft-hand extender base. General-purpose and transparent ink systems usually have one extender base that matches the viscosity of the majority of the inks in that series. Opaque extender bases are used when the color intensity of an opaque ink must be reduced, but not the opacity. Soft-hand extenders are used to soften the printed image when opaque ink is to be used on a light garment. In most cases, opaque extender bases are used in small amounts up to a ratio of 1:1. Soft-hand extender bases can be used in ratios as high as 3:1 with very opaque inks. Soft-hand bases also significantly reduce the viscosity of heavy opaque inks, which is very desirable because it helps to reduce ink-film thickness. With a thinner deposit, prints can be cured more quickly, and productivity increases. While it’s possible to use extended opaque inks on light garments, the components that make the ink opaque will limit the brightness and intensity of color you can achieve. Ultimately, you’ll get the best results by using a general-purpose ink on light garments, rather than a highly opaque formulation. The other caution to keep in mind concerns the use of extender bases with process-color inks: Only use transparent half-tone bases that are recommended by the ink manufacturer of the process- color ink series. Ink handling and disposal Now that you’re familiar with the types of plastisol inks available and the kinds of jobs they’re designed to support, it’s time to consider the procedures you should use when handling the inks. The issues of greatest concern include mixing the inks properly, avoiding contamination, and reducing leftovers. Ink mixing Plastisol must be mixed at low speeds to avoid friction. If there is too much friction, heat will be generated and the ink will actually begin to cure where it is in contact with the mixing blade. This can be especially dangerous when using drill-type mixers, which is why I recommend working with low-speed paddle mixers. Several brands of ink-mixing equipment are available that employ paddles and support 1-5 gal of ink. Put a lid on it Invariably, shops will have more ink containers than they do lids to cover them. For some reason, many printers feel that once an ink container is open, there is no need to place the lid back on it (Figure 1). I heartily recommend that you avoid this practice. Lids serve a very important purpose. Anyone who has even visited a textile-printing operation knows that there is a lot of dust and lint in the shop. When these particles get into the ink, it can have a significant, negative effect on the ink’s usability. To see the impact of dirt on your inks, take the top layer of ink from a container that has not been sealed for a long time and try to print it through a medium- to high-thread-count screen. You’ll find it difficult just to get the ink to clear the mesh, and you’ll probably need some type of screen-opener product to get rid of dirt particles that block the mesh openings. Controlling ink waste One of the best ways to control ink waste is to use a color-matching system. Most major ink manufacturers have at least one Pantone-approved or simulated-Pantone color-matching ink line. The advantage to these systems is that they allow you to mix exactly what you need for an order. With a little practice, most ink departments can cut their waste more than 50% by using a color-matching ink system. The newest types of matching systems are medium in opacity and are designed for use on both light and dark garments. They can be used without modification on light-colored substrates and with an underbase on dark substrates. The newest software for these matching systems actually includes work-off calculations. Users enter information, such as the ink weight and Pantone number of leftover ink, and the software calculates what additional colors can be made from the leftovers. Even with solutions like these, you may still have some leftover ink that you cannot find a use for. In this case, sort the leftover ink into containers based on color. You’ll need two or three waste containers. In the first container, put any scrap inks that contain little or no white pigments. Fill the second container with inks that contain white pigment. In the third container, pour the oddball scrap ink, such as puff, metallic, shimmer, and other special-effect inks. When you have a couple of gallons of the first container, you can add a small amount of black pigment and use the ink in non-critical applications. I recommend that it be used for simple one-color jobs. I have seen the black pigment bleed into other colors when it makes contact with them on a wet-on-wet print, so it is best to keep the black pigment isolated. The second bucket can sometimes be blended together to produce interesting light and medium shades. Sometimes, you may come up with useable colors by blending in some fresh ink. It is a potluck situation. Remember, because high levels of white ink are present, new ink mixtures made from this second bucket will always be quite opaque. The third bucket is truly waste ink. In its liquid form, plastisol is considered a hazardous waste in most jurisdictions. However, when it is cured, it is not considered hazardous. Spread a generous scoop of the scrap ink on a piece of scrap cardboard and run it through the dryer several times. Once it is cured, it can be tossed in the dumpster. Organizing the inkroom The final steps in establishing control over your plastisol ink usage are to make sure all containers in your inkroom are labeled with details about the mixtures they contain (Figure 2) and to organize your ink inventory in a logical manner (Figure 3). These are the simplest methods to prevent ink-mixing errors and reduce waste, yet they are the most frequently overlooked by printers. First, let’s look at ink-container labels. All color-matching ink systems come with software that provides color-mixing formulas, as well as a utility for generating a label with details about the components used to create the mixture. If you don’t use such a system, then you can create labels by hand. The labels should list the color of the ink mixture (ideally with a swatch of the color), what components were used to create the mixture, how much of each component was used, and the date the mixture was created. Any special characteristics that mixture has, such as bleed resistance, also should be noted, as should the opacity level. Once all your ink containers are labeled, it’s time for the second step, which is to divide your inventory into the following groups: 1. ready-for-use factory containers and unmodified inks 2. low- to medium-opacity mixtures 3. high-opacity mixtures 4. ink modifiers If you do a lot of athletic or special-effect printing, you may want to establish additional sections for athletic or specialty inks. After you sort the inks into these general categories, organize them by color and actual opacity level. When your inks are separated in this manner, you’ll more quickly be able to find the right formulations for a particular job and verify that an adequate inventory of each ink type is on hand so that you can avoid substitutions. Then you can begin calling out the inks by their label name on job tickets and get the right colors and opacities for the job without guesswork. The result will be inks that match the substrate and screen thread count and jobs that run more smoothly. Ink is not the most expensive component of an imprinted garment, but it can be a huge drain on your bottom line if you don’t match your applications with the right ink mixtures. The only way to ensure that you use the right inks for each job you produce and avoid ink waste is to maintain an organized ink inventory and document critical information on ink containers. Being able to find the right ink with minimal effort will lead to lower costs, higher productivity, improved color matching, and fewer rejects for your operation. And in the end, you’ll realize higher print quality and happier customers.

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Screenprinting Magazine.

Most Popular

-

Case Studies2 months ago

Case Studies2 months agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns3 weeks ago

Columns3 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?