Garment Printing

Published

13 years agoon

If your main goal is speed, the end result is rarely ideal for a consumer product. The extra speed you obtain when you fail to consider quality or waste is lost quickly when you have to redo part or all of a job. This mentality is the same when considering the separation method that you use to process an image for screen printing.

If your main goal is speed, the end result is rarely ideal for a consumer product. The extra speed you obtain when you fail to consider quality or waste is lost quickly when you have to redo part or all of a job. This mentality is the same when considering the separation method that you use to process an image for screen printing.

Raw speed in separation doesn’t guarantee quality on press. This is one of the reasons why it is difficult to script the separation process with preset commands in Adobe Photoshop. Each image that is presented for separation has its own ideal color palette, and some adjustments must be made to prep a file before pulling out the right colors. After that, you have to select the right separation methods for the specific image.

Speed is still important in separations, of course. The ability to separate an image in 15 minutes instead of two hours yields production time that can be allocated to other areas. Additionally, too few screen printers charge adequately—or at all—for the separation process, which makes any delays costly.

A fast separation set may not be completely successful on the press on the first setup. Experienced printers know spending a little more time on quality separations makes for higher success rate during production and less downtime. Separations that fail on press are very expensive, no matter how fast they were done. How can a printer have fast separations that are also very reliable the first time they are put on press?

The best way to decide which process is ideal for a specific screen printer is to review some designs with three different separation methods and compare them to their individual speed of execution, accuracy of reproduction, and rate of success on press.

To keep it simple, the three different methods of separating detailed artwork are simulated process, four-color process, and index color. Determining which method of separation produces the fastest set of quality screens depends on several factors: preferences in the production and art departments, image variables, equipment limitations, and separator skill.

Art preparation

Preparing files for color separation is one of the most underrated activities in the art department. The artist may not know how or have the experience to prep the file, the designer may not want to revisit the work before separation to avoid looking inefficient, and there is always the communication process that needs to happen between the art department and the sales department when the look of the artwork is adjusted. These issues may cause a design to go to separation with a lot of inherent problems that will cause significant separation challenges or may not show up until the screens go onto the press. Deal with your art and separation problems before pulling out colors. Colors become more difficult to define once the separation process starts.

Prepping an art file for separation involves reviewing it in three major areas: color pollution, resolution and file size, and edge quality. Once you review and correct for all of these aspects—if necessary or applicable as budget and time permit—the final colors are almost always easier, clearer, and simpler to duplicate correctly in a final print. Here’s a quick look at the three areas of art prep in regard to how they contribute to the separation process:

Color pollution This is the one of the least addressed areas in prepping artwork. Ironically, it is also one of the easiest to correct. An image that appears at a distance to have a flat area of color may, upon closer inspection, have a lot of colors that are crowding together to effectively pollute the intended color (Figure 1). Separations may have a lot of holes in the solid areas of color when this color is pulled, and extra colors may be ghosted onto other screens where they don’t belong.

A good solution for images that show significant color pollution is to use the layers dialog in Photoshop and then select the main color that you are looking for using the eyedropper tool. You can then adjust this color to the right hue by selecting it from the tool menu and then modifying it in the color-picker dialog. Once you have the proper color for separation from the design, you can use the color-range command in Photoshop on this color to select all of the areas in the image that have this color. Careful use of the fuzziness slider in this dialog box will ensure that you select the right amount of color. Once you create this selection using the color-range tool, switch to the channels menu, and create a new channel by selecting the box at the bottom of this dialog. Fill the selected areas in the new channel with white—assuming you have the new channels in solid black—and then deselect the selection.

The next step is to invert this new channel and then use the curves menu to adjust it so it is very solid black. You can do this by pushing the black point most of the way along the bottom toward the white point in the curves menu. This creates a solid selection area in the channel. The new channel can then be used as a gross selection to create a new layer or adjustment layer in the layers palette. Just control-click (Cmd-click on the Mac) on the channel image in the channel dialog to select the white areas, then invert the selection. Go to the layers menu and, with this selection still active, copy and paste this area into a new layer.

The next step is to use the hue/saturation dialog and average the color in these areas of your new layer by using the colorize command. This new, colorized layer can then be adjusted by opacity or by using a layer-blend mode to merge with the original image underneath. It will force the selected colors into the same family/hue set (Figure 2).

Though this process sounds complex, it’s really just using a pre-selection to create a more precise selection and then averaging the color of these areas in a new layer like a lens on top of the original artwork. This process alone can reduce the number of colors necessary in artwork dramatically and improve the overall look, separation, and printing of images with color pollution.

Resolution and file size Every printer wishes that customers would provide original artwork ready to go onto the screens, but the reality is that only a small percentage of the artwork provided is considered ready to separate. More often, artwork is supplied that was compressed for Web viewing to 72 dpi and at a small size. These files—if they’re not rejected outright—must be adjusted, averaged, or in some cases completely redone. Low-res images don’t retain enough information to create a definitive separation set.

If the file is borderline and the client cannot provide a better source, then you can do several things to enhance your results (Figure 3). One solution is to take the original artwork and then up the resolution in the image/size dialog box to 200-250 dpi at the final output size. Review this ramp-up of the resolution carefully to see whether there is enough information to justify investing more time in the art.

Pay special attention to type clarity and sharp-edged lines in the artwork that may have appeared jagged in the low-resolution version of the file. If the file looks like it can be saved without a ton of work, then the first step is to copy and paste the image in as a new layer and then use the curves command to force the contrast up by pushing the white and black points together. This removes some of the marginal values that may have been created when the resolution was increased and define the edges better.

You can also define and edges manually, if necessary, by using Photoshop’s smudge, eraser, and brush tools. Finally, depending upon the image, you can copy the adjusted layer, paste it, run the poster-edges filter on it, and then adjust the opacity and blend mode so that just the edges merge down and help to define the original. Different options may be used depending on the colors and graphics in the image. Running through the layer-blend modes using the arrow keys is a good step here (Figure 4).

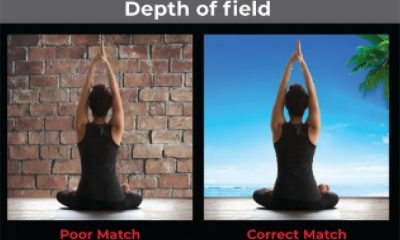

Edge quality The definition of the edges in an image contributes to its overall resolution. Many photographs that are used for designs to be screen printed are just plopped into a layout in Photoshop. These images may suffer from poor definition or unclear transitions from one shape to another in the graphic.

Solutions to poor edge quality in designs are complex and can take many forms, such as redrawing parts of the graphic, resetting type on top of fuzzy letters, and adjusting resolution selectively. You can also improve edge definition in a photograph by drawing on top of the original artwork in an extra layer using a fine black line to cut out shapes and define edges in the original. This works so well in screen printing because the black line knocks out a hole in the underbase or other colors, which helps to control ink gain, and the black line makes for a clean look on a printed shirt and gives the eye a place to stop.

Testing separation speeds

How fast can a separation run and still maintain the quality needed on press? Let’s look at what happened when two test images were processed through three separation methods that should work as quality processes for reproduction in screen printing (Figure 5). The results for simulated process, index color, and four-color process followed a predictable pattern with a few interesting exceptions.

Each method of separation has its advantages and flaws. The tests proved that expected variables would appear on press. The results of the speed tests of the prepared artwork were reviewed for time that it took to achieve final separations, number of colors necessary, and other considerations related to production.

Four-color process

Separating the images for four-color process was deceptively easy. The files were just converted from RGB into CMYK with black at maximum. The part of the process that took the most time was looking over the images and making adjustments to the sections or areas of color that wouldn’t print properly. There was a tendency for the separations to have too much black in them and some unnecessary ghosting of cyan and yellow in the red areas, so these had to be corrected manually prior to finalizing the channels.

Separating the files into four-color process with the added time for correction took 35 minutes each. The number of colors was four with an added underbase color for dark shirts.

The critical consideration is that four-color process requires intense control of press, ink, and garment variables to have a consistent look to all the garments through a printing run. These concerns make four-color process a big challenge for many screen printers. This approach to color separation is image dependent. Many printers won’t touch a four-color job on dark garments because of all of the headaches, but on white garments, with the right artwork, this style of printing can capture the widest array of colors.

Index color

Both of the test designs happened to be good candidates for index separation, so the test in a sense wasn’t quite as balanced. Index separations require a good understanding of how to manipulate an image’s color table in Photoshop as it is converted to an index-color design. Therefore, operator experience can really play a factor in separation speed.

Index separations are the fastest of the three types of separations discussed here. The final results for both designs were obtained in less than ten minutes. The time included some significant tweaking of the color table to allow for some blending and some underbase extraction.

One downside is that index separations take two to three times as many colors to work as the other methods—in this case, eight or nine colors each. The other major concern is that all of the colors are opaque in an index print, so nine colors were mixed to match what was in the file separations.

The flaws and advantages of index prints really go along with a shop’s production style. If a printer has a large press with a lot of mixed inks already, that might be a perfect environment for index printing.

Simulated process

The most popular style of separations for detailed art is defined by its ability to blend and create multiple colors and be friendly in production with minimal gain. Images can be adjusted to fit stock inks, thereby saving on mixing time.

Another advantage of simulated process in these tests was the ability to limit colors to six on both designs. The production of simulated process is more of a challenge in screenmaking than it is on press. Screens have to be made carefully to capture any subtle dots and shades to prevent loss of details in the design.

The drawback of simulated process is the time it takes to separate effectively. Even with a small amount of scripting—it’s easy to program a list of commands to create an underbase and highlight color—the separation of the test designs took 45 minutes each. Considerable adjustments were made to the final separations to ensure proper testing and printing without difficulty.

Summing up the results

The overall review of the different separation methods for speed and quality showed that while simulated process produced the best balance in profitable prints, it was the slowest in separation. Index color was worth a second look just for the fact that it is exceedingly fast to do—but it does create extra colors and needs a lot of custom inks. Four-color process was the most troublesome on the press and the most nerve-wracking for a learning screen printer to separate. In considering all of the test results, simulated process still leads in overall quality and printing ease; index color comes in a clear second for its extremely fast test times; and four-color process remains in last place because of its temperamental results.

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Screenprinting Magazine.

Most Popular

-

Case Studies2 months ago

Case Studies2 months agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns3 weeks ago

Columns3 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?