Garment Printing

Published

18 years agoon

Garment printers’ attitudes about producing a soft hand on dark garments have changed over the years. Most printers in the early 1970s didn’t give much thought to the hand because the wood and tubular-aluminum frames that were standard at the time didn’t give them much control over how much ink they were printing.

The introduction of the retensionable frame later in the 1970s represented a true jump in minimizing the hand on dark garments. But these frames were slow to penetrate the market because of their relatively high cost compared to traditional static frames. Over time, however, retensionables became a standard fixture in most textile screen-printing facilities, especially in shops that wanted to achieve higher levels of quality. Retensionables allowed printers to dramatically reduce the overall ink-film thickness of the prints, and by the late 1970s and early ’80s, the industry experienced some of the softest prints ever produced on dark garments. Soon mass-merchandising buyers began to seek out products that had these characteristics.

During the next decade, the importance of a soft hand began to wear off, and garment buyers started to consider the graphical impact of the garment much more than the hand of the print. More recently, the introduction of high-density plastisols has led the industry further away from trying to produce the thinnest ink film possible. Instead, the goal with these inks has been to find out how thick the printers can stack their inks onto the surface of garments.

Despite new trends, dark-garment printing with standard plastisols is still in high demand. And achieving a soft print is still an important concern for shops that want to ensure pleased customers and keep their costs under control. In this installment, we’ll review the processes and procedures that are required to produce quality images on dark garments while minimizing the overall hand of the prints.

Engineering the artwork

I have always been an advocate of the “less is more” theory. In relation to decorating dark garments, this means printing the greatest number of colors with the least possible number of screens. You can only meet this goal when you properly engineer the artwork. I also maintain that the best graphic artists in the garment screen-printing industry are those who have a solid background in screen printing onto textiles and have a solid understanding of the nature of the process. They must know the inks—how they work, how they mix—and screens, such as the various mesh counts and their impact on the reproduction of graphic and the quality of the print.

The artists who believe that if you have a 14-color automatic press, all of the heads have to be filled to achieve a quality print, are only decreasing the productivity of the shop and adding to the cost of printing and finishing garments. In today’s market, garment screen printers must make some changes to their priorities. They must concentrate more than ever on producing the effects that the customer is looking for and doing so in the most efficient and productive manner possible. This means engineering the artwork to satisfy the client, using the fewest colors possible, maximizing productivity in prepress and in production, and minimizing waste.

Underbases and flashes

I’ve dedicated previous installments of this column to writing about how important it is to get out of the mindset of always printing a white underbase. The point here that many printers overlook is that it takes more white ink to properly cover a black or dark garment than it would a light-colored garment, and that means higher costs. But if you can use another color from the graphic as an underbase, you’ll be able to print a thinner colored ink film through a finer mesh, flash faster, have less after-flash tack, and minimize the hand—all in one simple procedure. You can always come back and print a highlight white last for those areas that require it. Although this process does not apply to every graphic you’ll print, it can help you simplify many jobs, save time, and make more money.

Mesh selection and screen tension

If you want to produce a softer hand on a dark garment, then you have to make a priority of minimizing the ink film. You should start by determining the finest mesh count you can use to generate high-quality prints. Finer is better. When printing a simple, one-color design onto a dark garment, many printers will double stroke a 110-thread/in. mesh or print/flash/print with that 110-thread/in. mesh. In most cases, you can use the print/flash/print method with a print produced through a 230-thread/in. mesh. You’ll produce the same level of opacity, but further minimize the ink-film thickness. On a multicolored graphic, you not only need to determine which color to use for an underbase, but also which mesh count will work best in that application. Once again, a knowledgeable graphic artist should be able to make such determinations during the separation process.

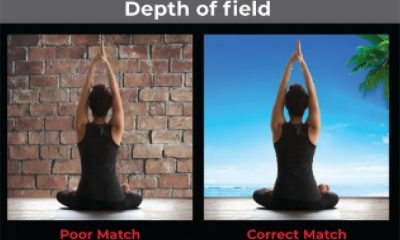

Screen tension has a big impact on the thickness of the ink film and, consequently, the softness of the print. Even though I know garment screen printers who have made a science of printing with either wooden or aluminum frames, the sad fact is that over time, those screens will lose tension and will gradually lead to an increase in the thickness of the ink film they lay down. The higher tensions you can sustain with retensionable frames allow you to use minimal squeegee pressure and deposit ink onto the surface of the fabric, not force it into the fabric as is the case with low-tension screens. Flash times increase and the hand becomes more harsh when thick ink films are printed into the fabric.

Special effects

Special-effect inks can blow all hopes of soft hand out of the water. You can, with practice, achieve a soft hand when printing some fluorescent, metallic, and crystalline inks, but you’ll fight a losing battle when you put high-density and glitter inks on press. The particle sizes of the polyester flakes used in today’s metallic and crystalline products still allow you to print a relatively thin ink film and maintain a moderately soft hand on the fabric’s surface. But high-density applications rarely will accommodate a soft hand, especially in jobs that require thick stacks of ink.

For any garment screen-printing facility, producing a softer hand is a matter of controlling variables, the most important being screen tension and off contact. Although higher end printers who work with halftones and multicolor images are more likely to place an emphasis on the hand of the garment than those who print athletic apparel, all screen shops can benefit from minimizing ink-film thickness on all jobs. Saving time, ink, and energy use are just a few of the benefits. You also can safely assume that most paying customers don’t want a heavy layer of plastic on the surface of their garment, so keep customer expectations high by keeping your ink deposits low.

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Screenprinting Magazine.

Most Popular

-

Case Studies2 months ago

Case Studies2 months agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns3 weeks ago

Columns3 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note3 weeks ago

Editor's Note3 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Marshall Atkinson3 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson3 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

News & Trends2 months ago

News & Trends2 months agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?