Andy MacDougall

The Fabric of Art

Published

14 years agoon

You know you are on to someone with an interesting background story when he answers an inquiry about his favorite jobs by relating the story of painting actress Cloris Leachman in the nude. Not a nude painting—they actually body painted Cloris, a long time friend and client, for a photoshoot for a health magazine. It took 14 hours. It was an experience. What’s that got to do with screen printing? We’ll get to that.

Arena Design has operated from the Houston area for more than 20 years. You won’t find their products in the local Home Depot, but you will find them gracing the homes of the rich and famous in magazines such as Architectural Digest, Interiors, Veranda, House Beautiful, Southern Accents, Elle Décor, and various coffee-table books. This company is well known and respected in the U.S. and worldwide in the upper echelons of the interior-design and architectural circles for its original patterned wallcoverings, fabrics, and floorcoverings, which pay homage to ancient tapestries or classic Fortuny designs—but are all original and made in the USA. They’re represented to the trade through exclusive design showrooms in major cities, but I should warn anyone who might be thinking of remodeling that, unless you have an unlimited budget, you should probably skip this article right now.

Portrait of the artist as a young man

The unassuming guy behind the company is Rusty Arena, born and raised in Houston by parents who migrated west from New Orleans. “Both of my parents were encouraging with any and all creative endeavors by me and my two brothers, Ron and Randy,” Arena says. “I remember my mother liked to sew. At around the age of five I was busy gathering bits and pieces of fabric from under her sewing machine. I glued my favorites to paper for no apparent reason, and then added a little paint and crayons. When asked what I was doing, I replied, ‘I don’t know.’ That was my first creation that I remember.”

Summers were spent in New Orleans visiting his favorite aunt, Ann, who would buy art supplies for him. His grandmother had a cool, funky apartment in the Quarter, and he was inspired by the art and architecture of this section of the city. He developed a love of the old, interesting patina of time, which found a deep resonance in his heart, even as a young boy. Weekends growing up in Houston were spent at one of two places: sunny days at the Zoo, and cloudy days at the Museum of Fine Arts. Saturday art classes at the MFA encouraged him to think about spending his life making art. He was right.

A self-described “victim of parochial school” and not doing very well in junior high school, Rusty lucked out when he enrolled in Houston’s High School of the Performing Arts, one of the first of its type in the U.S. “This school saved my life; it provided the structure for me to blossom. I received a wonderful exposure to the city’s diverse ethnic and cultural differences that help to develop a deeper appreciation of people and art. I knew at this point there were no other options but to pursue my dreams. I received scholarship offers from California Institute of the Arts, Rhode Island School of Design, and Parsons. To this day, I sometimes wonder what would have become of me had I accepted.”

Instead, he chose to stay in Houston and accepted a scholarship at the Museum of Fine Arts. He took his first real printmaking classes and learned the lithography, etching, intaglio, and serigraphy skills that he would put to use in the future. From an early age he had uncanny technical drawing abilities; rendering lifelike realism was easy. Unfortunately, one instructor at school was frustrated by the ease with which Rusty rendered life drawing models. To emphasize a more passionate approach, he grabbed Rusty’s hand, charcoal still clutched, and wildly scribbled over his drawing. “It really pissed me off,” Rusty remembers. “I was then given a can of spray paint and a piece of brown paper placed on the floor, then instructed to proceed with the study of the nude model. If I recall correctly, I mumbled a slew of profanities and then promptly left class.”

AdvertisementRusty took the can of spray paint home and used it to paint a cabinet, still frustrated with the entire episode. He then started in with a putty knife, scraping the wet paint off, revealing the color beneath. ”Voila! A new means of expression,” he recalls, laughing about the whole thing. “No one was really doing the distressed look yet. Faux finish was not a household word back then.”

He took a chance and opened a retail studio for creating all forms of art—not just pictures, but functional art: folding screens, furniture, lighting, and sculpture, always experimenting with the finishes, mixing patina and pattern and classical influences in a new way. Teaming up with his brother Ron, also an artist, and backer Delores Mitchell, they produced an array of one-of-a kind treasures. The shop was one of the first producing this type of material in the U.S. and gained the attention of New York Madison Avenue retailer Janet Carrington, which led to the creation of a new collection of functional art to sell through her shop. In addition, they began to receive commissions to create murals and trompe l’oeil in residential and commercial venues all over the country.

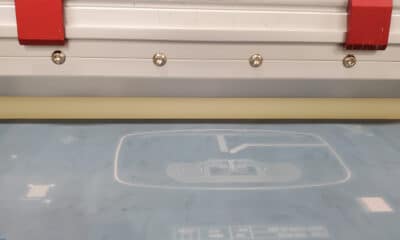

Although more successful than they could imagine, Ron left to get married and pursue his education, and Rusty closed the Houston shop and moved to New York to be closer to the center of the design world, which included a lot of parties, the Studio 54 scene, and rubbing shoulders with Warhol and the rest of the 1980s art and rock-star world. In 1986, ready for a rest and to refocus on the business of making art, Rusty returned to Houston, rented a loft, and began to paint. This started a chain of events that eventually morphed into today’s operation, housed in a former steel-fabrication plant that was purchased three years ago, thereby ending 20 years of renting space and moving 100-ft tables (Figure 1). Here, he and his long-time crew print his designs on rolls of paper, fabric, and other materials, producing orders for yardage from his catalogue of more than 300 existing designs and variations, taking on custom work, or working on new creations, applications, and techniques (Figure 2).

A short history of wallcoverings

Screen-printed wallcoverings are nothing new. Like many of the range of products made with the screen process, this industry sector existed in Japan and China long before it made an appearance in Europe. Originally handpainted, wallpaper manufacturers tried to imitate fabric coverings by offering an economical alternative that was printed using wood blocks and hand coloring. English wallpaper dates back to at least 1509, where a remnant discovered in 1911 was printed on the back of a proclamation by Henry VIII. Examples from the following centuries are found in England, France, and other European countries, where it became popular among the rising merchant class and grew more ornate and colorful over time.

Innovations in production brought stenciling into the mix, used to apply repeated color areas and shapes. Flocking also appeared in the 1600s, and colored papers were introduced from China by the beginning of the 1700s. Multi-panel designs became more common. Governments jumped on wallpaper as a tax source in 1712, nailing domestic producers as well as imports. This didn’t slow down the industry, but it did result in a law making falsification of a government wallpaper stamp a death penalty offence in 1806. The English took their wallpaper seriously back in the day.

Finely detailed wallpaper was imported from France and England into colonial America, and a home-grown industry sprang up during this time period. Producers kept adding new elements and design motifs, in-cluding borders and large panoramic scenes made from 20-30 intersecting 10-ft x 20-in. panels. The repeal of the wallpaper tax in 1836 led to an explosion in demand and the patent for the first wallpaper-printing machine in 1839. Screen printing became widespread as a production method in the 1920s, and designs changed to suit the tastes of the times. Vinyl wallpaper was introduced in 1947, pre-pasted papers in the 1950s, and high-speed rotary screen-printing presses in the 1960s. This transformed the long, hor-izontal step-and-repeat systems that were the standard in decorating fabric and wallcovering for centuries into a high-speed, high-output roll-to-roll operation.

AdvertisementIn today’s industry, which is estimated to generate around $2 billion annually in sales in the U.S., there are three subsectors. The largest is for mass -produced patterns, mostly made offshore on high-speed, automated, rotary screen presses or by web-offset printing, with product targeted at the domestic housing market. Wallpaper competes with paint as the finish of choice. So it comes down to price, fickle consumer tastes, and the demands of the renovation and new home market.

The second distinct sector is a growing custom market fueled by large-format digital printers, which allow for photomurals and short-run specialty items or themed wallpapers for use in stores, offices, and homes. The final sector is also growing, and includes smaller boutique operations like Rusty Arena Designs, which uses old-school methods to produce its work. Characteristics of this sector usually include a combination of original and custom designs, 3-D or specialized finishes on a wide range of tactile materials, or classic patterns that evoke old-world opulence. Some companies specialize exclusively in reproducing classic and antique wallcoverings for restorations and historic landmarks. Although the smallest segment of the wallcovering business by sales volume and yardage produced, these custom shops earn the highest dollar per square foot for what they make.

Houston, we have a squeegee

A meeting with clothing designer Michelle Ballas led to a contract to create images to be printed on suede hides. They were an instant hit and produced requests for fabrics printed with more images, which in turn led Rusty to a Houston screen printer named Jim Wicker. According to Rusty, Jim was a great guy with an incredible sense of humor. He had to have one, as he had just gotten rid of a complete fabric-printing operation after failing to find a designer who could work in the medium and produce a high-end product. Here was an artist who had great designs, customers, and needed a screen printer. Talk about a day late. They both decided to give it a go and set about putting together a new facility to print 100-ft bolts of multicolor fabrics. There were two big problems—if you don’t count their business plan, which was essentially let’s make it and then sell it. They had only $1000 in startup capital, and the tables they needed wouldn’t fit in the existing

loft space.

After a detour into a basement that was dark, dank, and shared with an artist who kept 16 cats, the search was on to find an inexpensive, long-term lease where the partners could build their business. “I had a friend who owned a warehouse in the first ward, a very scary locale at the time but almost affordable,” Rusty says. “It had been an auto-repair shop for the prior tenant; we would need to clean the space thoroughly to produce textiles. By leasing the entire 40,000-sq-ft facility and parceling it out to other artists, we earned a greatly reduced rent. We had inadvertently started another artist community away from the downtown. A dozen additional art studios were eventually rented. This studio was to be our home for 20 years. It was demolished three years ago. I vowed never to rent again, found a large parcel of land with an existing metal structure, and am happily not planning on moving 100-ft-long print-ing tables again!”

Rusty’s other brother Randy got involved; he engineered and built the prototypes for the step-and-repeat printing tables and designed and built an ingenious mobile curing unit that used a series of interlocking gears to time the process and yield colorfast cures to the fabrics as they were fed through. Innovation, invention, and scrounging skills are common to most screen-printing shops when they begin, but ultimately the startup financing of Arena Design came from the revenues Rusty continued to earn from paintings and commissions received to create murals, trompe l’oeil, sculptures, and painted finishes in residential and commercial projects around the country. Feeling displaced and spending long periods of time in other homes and businesses motivated Arena to direct his efforts from creating the painted finishes on walls to applying them to rolls of paper and other materials in his studio.

It soon became apparent that if the company were to succeed, Rusty would need to spend more time in the print shop and less time painting scenes halfway across the country—the occasional job like painting Ms. Leachman being the exception. He also learned that good employees make or break the business.

Advertisement“We had hired a series of employees over the years, but it was exhausting to train new staff. My absence had a negative effect on the morale and quality—one needed to possess the passion to create and take pride in what was produced. Only one employee had all the required skills and temperament to stay working with me for the last 14 years. His name is Ruben Mason. Without his commitment, it would have been almost impossible to survive so many twists and turns in the road. He is currently the head of production. Tina Sloan is my assistant, which is not an easy task. Her job is to keep us on schedule, maintain showroom sampling, invoicing, and shipping. My other key worker is Jose Sanchez, a good printer and builder and overseer of the studio and adjoining property. It’s hard to put together a good team. I have one now and consider them to be extended family.”

Arena Design made a conscious decision to strive to create the finest unique hand-made products on the market (Figure 3), surmising correctly this would get his products noticed in the major design magazines. Rusty was inspired by Mariano Fortuny, a Spaniard living in Venice, who died in 1949. He manufactured some of the most beautiful fabrics in the world and was called the magician of Venice for transforming Egyptian cotton into opulent recreations of 17th-century handwoven silks. Other historical textile designs were lovingly rescued and preserved, thereby creating a legacy to which other designers can refer. The conservation of these antique patterns provides us with the basis of most traditional motifs we see today.

Fortuny’s fabrics are still produced in Venice, many years after his death, on machines he invented in the early 1900s. Many in the interior-design world consider Arena to be a latter day Fortuny. His commitment to excellence and innovation in the mixing of printing and handwork continue to produce articles, reviews, and spreads in all of the major interior-design magazines. This has led to increased sales and ongoing representation that has allowed him to grow and stabilize the business. Arena’s company purchased its own building three years ago—a major accomplishment—to better handle future challenges.

“As for the future of Arena Design, I think it will endure. I hope my dedication to preserving and developing new printing techniques will not be replaced by a computer-generated image,” Arena says. “I hope there will always be the real thing out there so people can choose. I’ll continue to edit through new technology, select that which is useful, and incorporate into a workable relationship with passion to continue growth. It is a joy to create; it is what I do, and those moments under my mother’s sewing machine playing with bits of fabric have become my life.”

Andy MacDougall

Andy MacDougall is a screen-printing trainer and consultant based on Vancouver Island in Canada and a member of the Academy of Screen Printing Technology. E-mail your comments and questions to andy@squeegeeville.com.

Andy MacDougall is a screen printing trainer and consultant based on Vancouver Island in Canada, and a member of the Academy of Screen & Digital Printing Technology. If you have production problems you’d like to see him address in “Shop Talk,” email your comments and questions to andy@squeegeeville.com

SPONSORED VIDEO

Let’s Talk About It

Creating a More Diverse and Inclusive Screen Printing Industry

LET’S TALK About It: Part 3 discusses how four screen printers have employed people with disabilities, why you should consider doing the same, the resources that are available, and more. Watch the live webinar, held August 16, moderated by Adrienne Palmer, editor-in-chief, Screen Printing magazine, with panelists Ali Banholzer, Amber Massey, Ryan Moor, and Jed Seifert. The multi-part series is hosted exclusively by ROQ.US and U.N.I.T.E Together. Let’s Talk About It: Part 1 focused on Black, female screen printers and can be watched here; Part 2 focused on the LGBTQ+ community and can be watched here.

You may like

Advertisement

Inkcups Announces New CEO and Leadership Restructure

Hope Harbor to Receive Donation from BlueCotton’s 2024 Mary Ruth King Award Recipient

Livin’ the High Life

SUBSCRIBE

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Screen Printing magazine's news bulletin.

Advertisement

Latest Feeds

Advertisement

Most Popular

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Case Studies1 month ago

Case Studies1 month agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Andy MacDougall1 month ago

Andy MacDougall1 month agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns2 weeks ago

Columns2 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?