Articles

The Fourth Disruption: Why Venture Capitalists Are Eyeing Garment Decoration

Published

8 years agoon

Some people look at the internet-based businesses that are gaining momentum in custom apparel and think that digital disruption has finally reached our industry. Not me: I’m used to being disrupted. This is my fourth rodeo. It started before many who are reading this were even born. When I got into the graphics industry in the 1970s, it was a highly evolved craft with specialists at many different levels. In many cities, there was a formal apprenticeship model and techs worked their way up to the journeyman level of proficiency.

Some people look at the internet-based businesses that are gaining momentum in custom apparel and think that digital disruption has finally reached our industry. Not me: I’m used to being disrupted. This is my fourth rodeo. It started before many who are reading this were even born. When I got into the graphics industry in the 1970s, it was a highly evolved craft with specialists at many different levels. In many cities, there was a formal apprenticeship model and techs worked their way up to the journeyman level of proficiency.

That all changed in the early ’80s with the introduction of the PostScript language and Apple’s release of the Macintosh personal computer and LaserWriter laser printer. Desktop printing was born. I still remember marveling at being able to choose fonts and print them out of the laser printer. That was 1984, and the world as we knew it took a sharp turn.

That all changed in the early ’80s with the introduction of the PostScript language and Apple’s release of the Macintosh personal computer and LaserWriter laser printer. Desktop printing was born. I still remember marveling at being able to choose fonts and print them out of the laser printer. That was 1984, and the world as we knew it took a sharp turn.

We needed to learn a whole new set of skills. Desktop computers were still fairly rare. It was a heady time as we raced to learn Adobe Illustrator. Then, in 1990, Photoshop appeared and sealed the deal. We could now scan art into the computer, adjust it, and output it through the laser printer. Customers stopped giving us crappy hand-drawn art and started bringing in horrible art created on the desktop in MS Word and PowerPoint. It was genuinely awful, but we persevered. We were still making camera shots, but soon we were evolving to have film output from the local service bureau.

1990, Photoshop appeared and sealed the deal. We could now scan art into the computer, adjust it, and output it through the laser printer. Customers stopped giving us crappy hand-drawn art and started bringing in horrible art created on the desktop in MS Word and PowerPoint. It was genuinely awful, but we persevered. We were still making camera shots, but soon we were evolving to have film output from the local service bureau.

Enter the second digital disruption: digital film output. By 1988, you could get your positives output from a Linotronic imagesetter, or color separations from a high-end, million-dollar Hell, Crosfield, or Scitex drum scanner. It was still very expensive – a typical set of CMYK color separations for a T-shirt cost about $350 to $600 – but it was clear that the days of the process and stat camera were numbered.

Enter the second digital disruption: digital film output. By 1988, you could get your positives output from a Linotronic imagesetter, or color separations from a high-end, million-dollar Hell, Crosfield, or Scitex drum scanner. It was still very expensive – a typical set of CMYK color separations for a T-shirt cost about $350 to $600 – but it was clear that the days of the process and stat camera were numbered.

The relentless digital march continued. By 1990, we saw the first computer-to-screen (CTS) systems, based on the patent from my friend and colleague Geoff McCue and brought to life by Gerber with the ScreenJet. It was slow, the resolution was low, and it was very expensive. It took another 10 years before all the bugs of CTS imaging were ironed out, but today, CTS is mainstream and continues to change the industry.

The third digital disruption came in the early ’90s when wide-format digital printing appeared. This technology spurred a huge renaissance in P-O-P printing. Screen equipment developers responded with the introduction of wide-format inline multicolor presses that sold for a million dollars or more, depending on size.

Inkjet stunned the designer community with its brilliant color, but it was so slow you could not scale the output for larger orders. It caused graphics screen printers to really buckle down and learn color management, CMYK halftone printing, and process control. Wide-format inkjet printers also further crippled the market for photographic services since screen printers could use them to cheaply make very large film positives. It made large CMYK separations affordable for much smaller runs.

Today, the digital printing revolution has decimated some of the traditional printing markets. Virtually every segment has felt the effect as run lengths continue to move toward a unit of one. The huge capital investments and associated run lengths required to make them economical have collapsed. Big litho printers have all made investments in wide-format inkjet and continue to cross the specialty graphics line.

The Changing Landscape of Digital Marketing

Now, 30-some years later, we find ourselves in the middle of the fourth digital disruption, this time in marketing. Access to data and new ways of leveraging it are changing the marketing industry in the same way that desktop publishing, digital film output, and digital printing once changed our businesses. Every phase of sales and marketing has been profoundly affected.

It’s a historic change that comes down to one very simple concept: Nothing happens until something gets sold. Digital marketing allows us to directly measure everything we do – every click, every page viewed, every action taken. For the first time, it’s possible to track the cost of our marketing actions directly to the point of sale. It can all be monetized. This has the potential to cause even greater disruption in our industry than any previous digital innovation. In fact, it is already happening.

You need to understand that digital marketing isn’t about social media, email campaigns, landing pages, and websites. It’s not about video, auto-responders, or any of those things. It’s about data – data that is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

You’ve probably heard the term “Big Data” but may not realize that you’re very much a part of the concept. Everything you do on the web, smartphone, and cable is being collected, filtered, and analyzed. Sometimes it’s personally identifiable; many times it’s anonymous yet aggregated. The data is being used in previously unheard-of ways. Non-relational events are being identified and the resulting behaviors revealed. Eventually, this process provides the companies that want to sell us things with incredibly powerful information.

This may sound a bit creepy, and in many ways it is. But it’s important to know that all of these data analytics are available to us too, right now, for super cheap. This is why everyone is jumping on Facebook, in particular, but also on Twitter, LinkedIn, and more. Every user can access the data behind each platform and use it for their own marketing efforts. It takes some work, and the learning curve is steep at first, but anyone can do it.

The bigger concern in our industry is the parties whom all this data is attracting. The previously unfamiliar world of quants and data scientists is landing directly in our backyard. Some really big fish are circling our little pond.

What the Escalation of Venture Capital Means

Venture capital (VC) is a type of financing earmarked for early-stage technology developers judged to have high growth potential. The people with VC money to invest have discovered the decorated apparel industry in a big way. They see it as the next multibillion dollar market they can disrupt.

VC money in our industry isn’t new. Some was directed to companies like CafePress and Zazzle as far back the late ’90s. Some of those investments made during the first dot-com bubble didn’t make sense, but they laid the foundation for the current generation of investors.

What’s different this time around is the size of the players. They are top-tier VC firms like Andreessen Horowitz, a $4-billion company founded in 2009 by Marc Andreessen (inventor of Netscape) and Ben Horowitz. The investors entering our market are the same ones behind companies like eBay, PayPal, Facebook, Google, Uber, Netflix, and other household names. We’re talking about the big guns.

These VC firms are placing chips on decorated apparel because they smell opportunity. They realized what I have been saying for years – that the printed T-shirt is a media of personal expression – and immediately recognized that matching demographics and data on personal interests had unlimited potential for connecting to apparel buyers. In a social media-obsessed world where everyone expresses their opinions on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and beyond, there could not be a better fit.

When you combine this with the ability to connect all the associated data behind each and every user, you have the equivalent of X-ray vision. You have the ability to know more about buyers than they know about themselves.

The VC business is all about two things: market disruption and customer migration. The firms want to show that they’ve changed the status quo in an industry and caused a massive shift to their platform. Here’s the scary part: They are betting tens to hundreds of millions on their investment and they don’t care if they make a profit.

This has huge implications. It means these firms can set up a new state-of-the-art factory that none of us could ever compete with, losing a ton of money on every job they run, and it doesn’t matter. The only thing they care about is the size of the market they are disrupting and how much of it they own. They’re focused entirely on driving new customers.

In the world of technology speculation, it’s all about valuation. Through some crazy, illogical formula, disrupting companies are valued at ridiculous multiples of their sales volume, not their profitability. Every VC firm has an eye on the initial public offering (IPO), where the company issues public stock and the investors hope for a hundredfold payout. Not every investment pays out at such a multiple, but we all have heard about people like Larry Page and Mark Zuckerberg, who became instant billionaires when their stock went public.

Venture capitalists cash out and leave the messy business of making the company profitable to someone else. Often, the disruption and lack of profitability continues for years after the IPO. It took Amazon nine years to show its first full year of profit in 2003. For what amounted to a penny a share of profit, they completely decimated the online retail space and continue to do so today. Their model is to starve the competition out of the market, and this time their sights are set on us – the small, independent apparel graphics producers.

What This Means to You

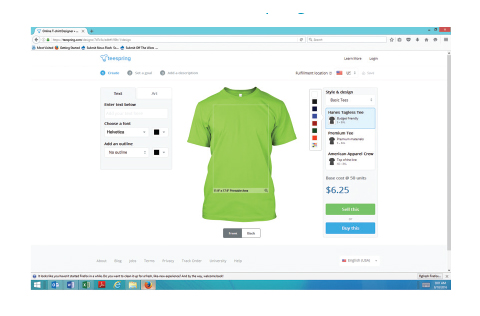

Right now, Teespring is the company to watch. Investments from Khosla Ventures and Andreessen Horowitz amounted to $55 million in 2014, and it’s showing incredible growth. They have figured out how to create a platform for independent marketers who think up a design and want to market it on Facebook and Instagram. They do everything – create the webpage, do the artwork, print the shirts, collect the money, ship the order, and pay the promoter share. They are already doing this millions of times a year.

Initially, Teespring contracted out all of its production to printers across the country. Then, they built their own 105,000-square-foot facility with a reported initial install of 23 automatic presses and 37 more planned. They concentrated on building their internet platform and e-commerce ordering and payment processing. A big part of the platform was its data acquisition and analysis.

The interesting thing about Teespring is that they own all the customer data, buying history, campaign history, collateral campaigns, and customer email addresses. Essentially, their promotion partners built all of that for them and pay for it with their promotion dollars. Oh, and by the way, they don’t share that information with their partners. Multiple people have become millionaires using this platform, and what they have in common is that they are marketers, not decorators.

Companies like CustomInk are doing it differently. They’re marketing custom apparel directly to groups and organizations on a national basis. CustomInk has built a solid brand that’s well-respected and followed. Until just recently, they didn’t do any of their own production, contracting it out to hundreds of printers across the country. Now, they’re building their own factories and bringing the work inside for themselves. In the fall of 2013, they received a $40-million investment from Revolution Growth, an investment fund headed by Steve Case, the founder of AOL, Ted Leonsis, and Donn Davis.

The thing to notice about both of these companies is their control of the customer base and the data. It’s very easy for them to evolve and migrate away from outside contractors. They’re building brands that are recognized and respected, with each doing hundreds of millions of dollars in business. You might think, “Yeah, but they’re huge and I’m just a little guy.” But the vast majority of their orders are 50 pieces or less. This hits squarely into the market of every locally owned decorator. We are witnessing the rise of what the big box stores like Walmart and Home Depot did to local small retailers.

To compete, you have to shift your focus from production to marketing. It’s all about being able to connect with and be relevant to your customers. As attractive as it may be for your customers to do business over the internet, a big percentage of them want to do business locally, especially if you can do a better job and deliver a personal experience. You see it all the time. I can’t tell you how many times printers have told me a customer comes in with a graphic they built on someone else’s design website.

The more you know about your customers and your market, the better your chances. You need to know the same things the new competition knows. Learn about Facebook Data and Ads Managers. Learn how to find and dominate specific niche markets. It’s a different game now, especially if your business is more than 15 years old. The new generation entering the industry was raised in a digital world. They are competing on terms they understand.

As hard as I’ve tried, I have not found one instance where digital disruption has entered a market and the old ways survived. I’m sure there are examples out there, but we are living in a world of digital Darwinism. Adapt or die. It has happened in music, photography, design, and video, and no area of our lives is immune. Consider what Uber is doing to the taxi business and Airbnb to hospitality. We are in the midst of the biggest economic shift since the Industrial Age began in the mid-1700s. There is more opportunity now than ever, but it comes at a price: Your willingness to pay attention, learn, adapt, and deliver.

Explore the rest of our August/September 2016 issue or read more from Mark Coudray.

SPONSORED VIDEO

Let’s Talk About It

Creating a More Diverse and Inclusive Screen Printing Industry

LET’S TALK About It: Part 3 discusses how four screen printers have employed people with disabilities, why you should consider doing the same, the resources that are available, and more. Watch the live webinar, held August 16, moderated by Adrienne Palmer, editor-in-chief, Screen Printing magazine, with panelists Ali Banholzer, Amber Massey, Ryan Moor, and Jed Seifert. The multi-part series is hosted exclusively by ROQ.US and U.N.I.T.E Together. Let’s Talk About It: Part 1 focused on Black, female screen printers and can be watched here; Part 2 focused on the LGBTQ+ community and can be watched here.

You may like

Advertisement

Inkcups Announces New CEO and Leadership Restructure

Hope Harbor to Receive Donation from BlueCotton’s 2024 Mary Ruth King Award Recipient

Livin’ the High Life

Advertisement

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Screen Printing magazine's news bulletin.

Advertisement

Most Popular

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy1 month agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Case Studies1 month ago

Case Studies1 month agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Andy MacDougall1 month ago

Andy MacDougall1 month agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns2 weeks ago

Columns2 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?