The Realities of Implementing Computer-to-Screen Imaging

Published

18 years agoon

The technology that has emerged in the past couple years for direct digital garment decorating could eventually influence traditional garment screen printing. Even though inkjet printing on T-shirts is the topic of a lot of hot conversation among medium to large textile printers, the number of functioning, productive, high-volume machines is still very low. But just as graphics screen printers have learned, our clients will, at some point, have multiple imaging options from which to choose.

The technology that has emerged in the past couple years for direct digital garment decorating could eventually influence traditional garment screen printing. Even though inkjet printing on T-shirts is the topic of a lot of hot conversation among medium to large textile printers, the number of functioning, productive, high-volume machines is still very low. But just as graphics screen printers have learned, our clients will, at some point, have multiple imaging options from which to choose.

To further complicate things, average order sizes have declined over the last few years. This is not unique to garment screen printing. The trend has infiltrated virtually all areas of the graphic-imaging community, including offset and the other printing processes. Many reasons for the decline exist, but the fact remains that turnaround times are shorter and jobs come in more frequently but are smaller. This spells economic chaos for the old-school printing model where order sizes are determined based on amortizing prepress and set-up costs.

Larger printers have been forced to move into the midsize market to replace the really huge orders they lost as more and more business has moved offshore. The number of print runs that exceed 1000 pieces has steadily declined as the competition for these orders has increased under the influence of the more aggressive, larger printers.

The only way to remain profitable in light of these changing conditions is to change the way we do business. In November 2005, I began the redesign of my shop’s business plan and the model on which it has operated for the past 33 years. Everything was on the line. Every process, method, and practice was put under the microscope and judged on its own merit. "That’s the way we’ve always done it" no longer served as justification.

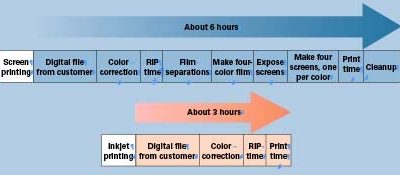

AdvertisementThe result was the creation of an accelerated production cycle where 72 hours is the standard order turnaround. We have provisions for next-day delivery when the client really needs it. In addition, we designed the systems around an order size of 50 pieces. To really appreciate what this means, you need to understand that we are 100% automated—no manual printers. Our minimum run size was previously 288 pieces. I effectively created a system in which we would need to produce a minimum of 20 complete changeovers per day in order to hit our breakeven. As crazy as this sounds, the increase in potential business was huge. This combination created new business in multiple market niches. But in order to get there, we had to completely change the prepress approach we traditionally used.

Computer-to-screen (CTS) imaging would be the foundation for this transition. I detailed the extensive benefits CTS technology offers in two separate columns last year (see "The Prepress Wire" in the July and October 2005 editions of Screen Printing). The major factor for me was the size of the shop and how to rationalize the more than $80,000 investment. After all, we produced 12-20 screens per day. We went some days without making screens because we were on press all day with orders in the thousands of pieces. I couldn’t justify such a purchase based on those practices. Instead, I focused on CTS’s enabling aspects.

A track record

I have used the premise of enabling technology very successfully in the past. The first time was when I made the decision to put automatic film processing into use. This was in the early 1980s when a fully automatic processor started at about $25,000 plus steep costs for consumables and daily calibration and maintenance. At the time, the shop tray developed with good results, but I wanted to get the chemicals away from the employees. Auto processing brought an entirely new level of quality and speed to our work and we were quickly able to offer technical film compositing and other services we couldn’t have previously considered. The investment paid off handsomely with new business we had never done before.

The second instance was the first occurrence of the impact of digital imaging on our industry. In 1991, I purchased a used Crosfield 646 digital drum scanner for $250,000. My shop was known for being a very good process printer, and I had outsourced all of our seps to a local offset house. When their volume increased, it became apparent our work would have to take back seat to their offset clients. While we could never justify the cost of a drum scanner solely for our own use, I quickly found we could sell almost a million dollars of separations a year to other frustrated screen printers like myself. We paid for the scanner, increased our knowledge and expertise, and added solid profit to the company.

We found ourselves faced with another prepress investment decision less than a year after the Crosfield purchase. All of this separation business burned a ton of money in compositing and assembly to final film. All of our scans were negatives, and we had to composite and convert back to positives. The process was slow and not particularly accurate. On top of this, programs like Adobe Photoshop and Quark XPress, which allowed for desktop publishing of traditionally high-end imaging, were becoming available. We were faced with a new challenge and ultimately made a $125,000 purchase of an Agfa Select Set 5000 drum imagesetter. It allowed us to digitally composite final film instead of using much less accurate manual image-assembly methods. We cut labor costs, shortened lead times, and improved registration film-to-film to ± 0.0002 in.

AdvertisementOnce again, these new capabilities differentiated us from competitors and business took a steep positive jump. Even though the investments were huge—even by today’s currency value—the size of the investment was declining. The Crosfield was more than $1,000,000 new, and we got a deal at $250,000 for a used one. The Agfa Select Set 5000 new was half the cost of the Crosfield. It gave us incredibly accurate films faster than anything we had ever used. After a relatively short learning curve, both pieces of equipment combined to form the foundation of our business model.

Enter CTS

Fourteen years have passed since the Agfa purchase, and we’re again faced with the challenge of justifying the purchase of radically new and expensive prepress equipment in order to capitalize on changing market demands. I could make a successful argument for the enabling aspect of the purchase of CTS equipment, but this time we’d be radically changing the entire way we handle information—and we would be doing it faster than ever.

The physical installation of the CTS device was no big deal. We built a new area for it adjacent to our current screenmaking area. The machine basically plugged in and was ready to go. The layout was different from our traditional screen room. Everything was closer together and much, much tighter (Figure 1). We designed the setup so one operator could image as many as 50 screens per hour (Figure 2). We achieved this level of productivity by balancing the capacities of each step of the process.

Each of our stencils takes roughly one minute to image (Figure 3). We expose stencils (30-40 sec with 5-kW metal-halide lamps and dual-cure emulsions) at the same time the next job is on the CTS system. Exposed screens go directly into a soak tank and are quickly followed with a high-pressure wash (10-15 sec). All of this works beautifully, and the equipment has consistently exceeded my expectations. We reduced the total time per finished screen from 38 minutes to less than six minutes. But that does not mean all is well.

Imaging and washout have been pretty much flawless, but other steps in the process have not been as easy to control—all of which relate to the pure digital workflow we now use. We no longer generate film, so the bulky job tickets we once used have been reduced to just the production-order information and print specifications. If we were to implement a documented digital workflow, we could eliminate this step as well.

Enter the need for a database makeover. Filemaker Pro was once our database of choice. We used it to store client information, job histories, estimates, orders, and invoices. We created work orders from estimates and invoices from work orders. We handled all of this in the front office before the tickets went to scheduling and the production departments. We used a pegboard scheduling system where 3 x 5-in. cards were filled out, punched, and hung on pegs for their respective due dates. This worked well when we handed fewer than 10 orders per day and the orders would stretch over a 10-day period.

AdvertisementOur scheduling system changed within 30 days of installing CTS technology. Order volume skyrocketed to 20 jobs per day, and they were all due with-in three days. We exposed 840 screens in our first month, compared to the fewer than 200 screens we handled the month before. This increase jammed everything into the front end of the process. The old system began to crash. Orders weren’t entered fast enough. Orders got lost. We had no way to handle multiple changes to the order.

In addition, we now had to deal with an entirely digital image-data workflow. Jobs would come to us by CD, e-mail, or over Internet-based file transfer. We needed some way to acquire and track the image files as they arrived. The fact that art frequently arrived from multiple sources further complicated matters. The art would often not be identified, so we’d have to track down the source and what job it went to. We would also have to deal with the usual preflight issues with fonts, images, resolution, and so on. All of this takes time, and we simply didn’t have it with this compressed order cycle. Stress levels rose faster than gas prices.

I was beginning to think we had created a monster. The staff was doing an incredible job of trying to hold it together. After all, my key people have all been with me for more than 20 years each. They knew the old ways perfectly and showed true bravery in embracing this radical, new approach. That only goes so far. We’ve operated a very controlled business for many years. I don’t like surprises, and I never want to disappoint a client because of a screw up. But where we may have made one or two mistakes, we were now making a dozen. Most were small, involving timing approvals and change orders, but the handwriting was on the wall. The system was creaking and groaning under the weight of the new workload. It was only going to get worse. And it did.

We built this digital workflow on top of our old database and ran it over a cobbled together LAN of 10BaseT and 100BaseT Ethernet connections. Most of our Macs ran Gigabit Ethernet, but the switches we used throttled the speed way down. We’re not network administrators. We all knew enough to make the system work, and that’s just the way it had been for years. Our setup was adequate for what we were doing, and nobody seemed to notice irregularities in the data flow. Our first clues appeared as the high network traffic began to get slower and slower. Moving files around seemed to take forever.

We shuffled more and more files between multiple workstations and various RIPs and imagesetters. Nothing was balanced or optimized. We had never checked individual machines or individual connections. On top of this, we’d been collocating our server at a local ISP, and it had been running for years relatively unattended. All of a sudden, I was learning about PINGing, hops, half and full duplexing, and a host of other network-related buzzwords. I very quickly found the need for new switches, routers, and servers. These things weren’t even on the radar when I first considered the CTS purchase.

Back to the database. The new CTS RIP delivered individual 1-bit TIFF files to the imager. In addition to this, we were also imaging many sets of simulated-process separations to film for our online separation business. Almost overnight, we were faced with what to do with hundreds of individual files that had been RIPed and imaged. We didn’t want to throw them away because we would have to reRIP each image in order to replace individual plates that may have been damaged, incorrectly imaged, or had suffered a mesh tear on press. We had nothing in place to handle these issues. In the past, we simply pulled the jobs off the individual machine and archived them to one of the hundreds of DVDs we have. We had film—and therefore little need to access the original images when a screen failed. Since the volume was low, it really didn’t matter when we reRIPed an image and sent just one color for new film.

We decided to handle the situation by setting up a new, dedicated database server offsite. It would allow us to move the final image data out of our building and off our existing internal servers for both safety and disaster recovery. You can imagine what a nightmare it could be if something were to happen on the internal servers and we were to lose all of the data. It became crystal clear that keeping the data onsite was a huge liability.

Establishing the database server also found us madly designing and programming an entirely new database model. The old one was based on an outmoded, flat, semi-relational model that worked well in a simple, single-user environment. The fact that the old system wouldn’t fit in the new workflow became instantly clear. Not only would the new database have to work over our internal network, but it would also have to be Web-enabled for access outside of our local network. After spending 100 hours doing new programming myself, I threw in the towel and brought in a certified developer, not so much because I didn’t know what I was doing (I can make it work, but without bells and whistles), but because I don’t have enough experience in designing scalable databases—those that work just as easily with hundreds of transactions a day as with 50 a day.

It just so happens that we ended up with a great guy who is also a network system administrator and SQL developer. SQL is a higher level database design that can be used to handled hundreds, or even thousands, of transactions per hour—an important feature. Now everyone inside the company, and many of our clients, can now access the database simultaneously over the Web.

An ongoing process

We’re almost four months into the transition and still doing a hundred different things at once as we continue this major system overhaul and upgrade. The impact on our business has far exceeded my expectations. I’ve hired eight more employees—the first new hires since 1998. Business volume is to the point where the shop handles more than 300 orders per month. The order volume has increased each month over the previous and shows no indication of letting up. Most importantly, we’re showing strong profit.

The investment in CTS was indeed an enabling point. It highlighted unforeseen weaknesses in our database, information exchange, archiving, and network servers—and it brought those points to the surface very quickly. But I would rather deal with everything from the get-go than have new problems appear every few days. The dramatic increase in screen-imaging capability forced us to step up in a much bigger way than I had ever imagined. We’ve strengthened most of our internal business-information systems simultaneously.

I have rarely seen such positive effects so rapidly as I did with this investment. Clients have embraced the faster order cycle, and the shop sees more orders more frequently than ever before. I am truly amazed by the amount of pent-up order demand in a market that has been basically flat for the last five years. Finally, moving to an all-digital workflow has positioned us to continue to be competitive with direct digital (for now) and to have the methods, means, and systems in place to transparently transition to other imaging processes as they become economically viable and feasible for production.

About the author

Mark A. Coudray is president of Coudray Graphic Technologies, San Luis Obispo, CA. He has served as a director of the Specialty Graphic Imaging Association Int’l (SGIA) and as chairman of the Academy of Screeprinting Technology. Coudray has authored more than 250 papers and articles over the last 20 years, and he received the SGIA’s Swormstedt Award in 1992 and 1994. He covers electronic prepress issues monthly in Screen Printing magazine. He can be reached via e-mail at coudray@coudray.com.

© 2006 Mark Coudray. Republication of this material in whole or in

part, electronically or in print, without the permission of the author

is forbidden.

SPONSORED VIDEO

Let’s Talk About It

Creating a More Diverse and Inclusive Screen Printing Industry

LET’S TALK About It: Part 3 discusses how four screen printers have employed people with disabilities, why you should consider doing the same, the resources that are available, and more. Watch the live webinar, held August 16, moderated by Adrienne Palmer, editor-in-chief, Screen Printing magazine, with panelists Ali Banholzer, Amber Massey, Ryan Moor, and Jed Seifert. The multi-part series is hosted exclusively by ROQ.US and U.N.I.T.E Together. Let’s Talk About It: Part 1 focused on Black, female screen printers and can be watched here; Part 2 focused on the LGBTQ+ community and can be watched here.

You may like

Advertisement

The Profit Impact of a Market Dominating Position

Inkcups Announces New CEO and Leadership Restructure

Hope Harbor to Receive Donation from BlueCotton’s 2024 Mary Ruth King Award Recipient

Advertisement

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Screen Printing magazine's news bulletin.

Advertisement

Most Popular

-

Case Studies2 months ago

Case Studies2 months agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns3 weeks ago

Columns3 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson2 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

News & Trends1 month ago

News & Trends1 month agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?