Business & Industry

Published

15 years agoon

Have you raised your prices more than once in the past year? If you haven’t, you are probably not making as much money as you should be. In fact, you are very likely losing money. For those of you who have not been paying very close attention, prices for everything are going crazy. As usual, it started with fuel costs and it is now trickling down to everything else.

Unfortunately, everything we do in business is somehow linked to the price of oil. When oil goes up, business costs can change rapidly. When oil makes one of its infrequent drops, business costs do not drop nearly as fast as they went up. The key for your business is that you have to be very cognizant of the increases in your costs so you do not get upside down in your pricing structure.

A good example of how to do it right is to look at the oil industry itself. Look at how fast and smoothly oil companies adjust to cost changes in their raw materials. Within days of news reports of the big jump in crude oil prices, we were already experiencing the result at the pump. When crude goes down we do get a drop at the pump, but at a much slower rate.

What prompted me to write this article was a discussion I had with a screen printer this summer. I reminded him of the increases that were working their way through the plastisol market and that it was probable that he would also see those kinds of increases in other facets of his business. His response was that he was having difficulty adapting as his customers would not accept a price increase on his work. At that point, I asked how he planned to stay in business if he was losing money on every order he did?

Customers always want the work for as low a price as they can get. It is a fact of life. At the same time, a business cannot survive if it does not make money. The printer in the previous example would actually be better off to not even print orders at the price he felt he was stuck working for. He would lose less money staying home and watching television.

A customer who will not accept reality by allowing you to make enough money to keep doing his orders is not a customer at all, he is a leech. That customer is only sucking the life out of your business to the benefit of his business.

Some accounting terminology

First, let’s define a couple of things. In this discussion, direct costs are those that contribute to the direct production of the product and therefore directly impact the gross margin. For a garment printer these items would be the ink, labor, shirt (if included), and the coating, exposure, and setup of the screens. If those items work out to 60% of what you can charge for a product, then the gross margin would be 40%.

Indirect costs are also known as overhead. These costs include rent, clerical and management salaries, utilities, and those supplies that do not directly help produce a product. These products might include cleaning solvents, reclaim labor and materials, mesh, frames, maintenance, and insurance.

Now let’s look at an example of that upside down situation I mentioned earlier. You’ll see why it is better to live without the type of customer who wants to be the only winner.

Imagine you have an agreed-to price with a major customer for $0.80/print for prints on their garments. This is a situation in the industry often referred to as contract printing (whether or not a contract actually exists). Six months ago, your gross margin on this work was a satisfactory 40%. Since then, your ink has gone up 12% and your emulsion has risen 10%. On the surface, this may be cutting your margin a few points. Unfortunately, there are other factors that are very much in play in the current economy. The rapid rise in the cost of fuel, solvents, power, and many other intangibles is hitting the indirect side of the profit equation.

Last year, a 40% gross margin may have carried forward to a 10% gross profit. But now, it may actually be a lot less than that. It is easy to see the way to proper pricing when just the direct factors are changing. It is much more difficult when the indirect factors are changing rapidly too.

An example for a graphics printer might be as follows: You agree to produce an order of 200 real estate signs on corrugated board. You feel you have a pretty good handle on the pricing as you adjusted for the recent 10% increase in the cost of the substrate and allowed for a 12% increase in the ink. However, what comes around to nail your profit is the increase in the price of the cleaning solvents, and the 40% increase in fuel, which subtracted from your profit because you offer free delivery to your local customers.

I spoke recently with a garment printer who offers free delivery to his customers. He said that his fuel costs had gone up more than $250 per month. That extra cost is weighed against a 15% reduction in sales due to the local economic slowdown. Taken individually, the fuel issue does not seem that terrible. But adding it to the other costs, such as utilities and insurance, and all of a sudden his gross profit had slipped to almost zero while his gross margin had been held constant.

Developing a quick-check monitoring system

Keeping up with all these changes can be daunting. A gas station has it easy. They have three to four products that they have to watch closely and they adjust prices every time the tanker makes a delivery. A full-service screen-printing operation has to look at a lot greater number of products. A textile shop may have 50 different garments that they print regularly, plus 100 inks, emulsion, chemicals, freight in, and indirect cost factors.

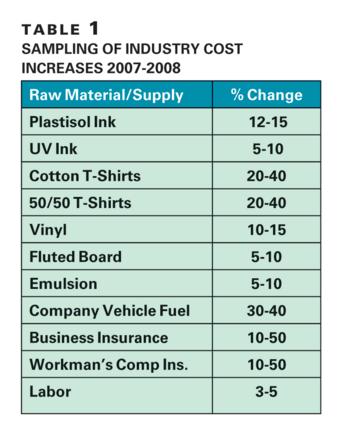

A graphics printer may have even a greater number of inks and substrates to consider. In addition, you might have a far greater need for outside services such as converting and application. These outside services are under great cost pressure too, and they are having to adapt rapidly. A list of several common cost items for screen printers and the increases they’ve experienced during the past year are shown in Table 1.

While most computer accounting programs will give you a nice month-end report to see what your company did over the past 30 days, that is too slow for the way some cost changes can sneak up on you. A larger company can easily monitor cost increases on a daily basis by just having the purchasing department chart the changes and report the jumps to management and/or the people who price orders.

For the small printer, with limited staffing, everyone has multiple responsibilities. For these companies that make up a major percentage of our industry a little more effort is required to make sure that they are current on costs. My recommendation is to utilize a spreadsheet that lists a number of key items. This spreadsheet does not need to make sense in total as we are not building an income statement. The numbers are just that, numbers. They are meant to work as an indicator of where things are today.

The spreadsheet function can be exercised every time you receive goods. By plugging the current costs as of that day, you will have a much better comfort level that you will not get a bad surprise when you run your monthly reports. The spread sheet shown in Table 2is what I recommend. This example is for a textile shop, but it can certainly be modified for any screen-printing or digital printing operation.

I set up this spreadsheet to include representative cost from last year plus each of the tests that I had run this year. That way, I not only see the cost today, but I see how it has changed and where it may be going. The numbers on the spreadsheet are not for specific orders but rather they are representative of the most commonly purchased items on the direct side and the most important cost factors on the indirect side. The snapshot they create does not relate to any order but to all orders. If I look at prices in October and my direct cost snapshot shows that my direct costs are up by 13% over December, but are the same as September costs, then I know that if my pricing in September worked out, then I do not need to increase it this month.

But, to be certain, I need to also see what is happening on the indirect side and there I find that Sept-Oct is flat. My pricing is fine…for now. When I move back in time to April/08, I see the biggest jump in direct costs and a slight increase in indirect. If I had not increased prices that month, I would have been upside down in a hurry.

Indirect costs are moderated by the fact that several of the biggest indirect costs do not fluctuate with the market. Rent and salaries are more predictable and since they are some of the larger contributors, they moderate indirect costs. But remember, if you only increase prices based on changes in your direct costs, you would see your gross profits go down even when you raise prices.

Customer awareness

The volatility of the current economy makes it imperative to stay on top of your costs. It is also a good idea to make sure your customers understand the issues you are facing. A smart customer will understand the pressures you are facing. They certainly have to be facing the same sorts of problems in their own business. If someone in business does not understand why costs are rising, that person is not playing in the real world.

In fact, this may be a great opportunity to see what your customers are really like—and whether or not they are worth having—in the long run. If a given customer is not agreeable to your need to make money, then they really are not much of a customer. Sure, they may bring your company a nice fat receivable every month, but do they make your company money?

Our industry seems to be plagued by the bad customer. The customer who can always get a better price down the street and even when you do get the order, getting paid is another story altogether. Working for a loss is not working, it is crazy. We lose enough companies in this business. Do not be the next casualty just because you were afraid to let go of a customer who was not willing to pay a fair price.

If you have a newsletter, email customer blast system, and/or a dedicated sales force, use these vehicles to keep your customers in the know about the pricing pressure that you are facing. Most of your own vendors are trying to do the same thing. No harm in copying their methods. I know of one major screen-print supply distributor that has a section on the home page of its website listing all the most recent price increases that they have had to enact. It makes it easy for their print customers to get a snapshot about how their own costs are likely to be affected in the coming weeks.

It is also a good time to avoid long-term, fixed-price contracts with customers. Unless you can secure your raw materials at a fixed price for the period of the contract, I would be very leery of a long commitment that does not allow you to adjust for your own cost increases. At the same time, customers would love to get a fixed price contract right now. For the same reason that airlines have been trying to hedge their fuel costs, a company that can fix some of their own costs can create quite a competitive advantage. Unfortunately, these advantages come at the expense of their suppliers. In this case, that supplier would be you, so be careful!

Keeping your business healthy

The ideas I have suggested here are not just good for the short term. They can be a good long-term addition to your bag of tricks for helping you keep tabs on your business. The value of the quick snapshot on costs is useful anytime. Even in an economy where prices and costs seem stable, why wait until the monthly or quarterly accounting reports to find out your profit margin took a dive because you did not react to a cost change on a major component of your business?

A good practice is to run the spreadsheet model any time you see a change in one item that you have included on the sheet. For instance, everything has been going along fine for months and, all of a sudden, your insurance costs spike. What does that do to your model? On our spreadsheet, a 15% increase on insurance would translate to a full 1% increase in indirect costs. If you were used to a 10% gross profit, that number just went to 9%—unless prices are adjusted.

I fully realize that we are talking about a perfect world here where everyone raises and lowers their prices based upon costs. In the real world, you also must face the competition that uses the cost pressure situation to gain market share by not raising prices. This situation is no different that any other day, it is just happening more frequently because of the cost pressure. Just remember, that the competition is experiencing the same cost increases that you are. Eventually, if they do not raise prices, it will hurt them.

You have to weigh the cost factors facing you and decide where your limits are independent of what the competition is doing. If you lose money on an order for competitive reasons, realize that you cannot do that forever, and neither can your competition. It is better to have a healthy smaller business than an unhealthy larger one that goes belly up.

Mike Ukena is a 22-year screen-printing veteran who has owned a textile-printing company and worked in technical services for the SGIA as the director of education. A member of the Academy of Screen Printing Technology, Ukena is a frequent speaker on technical and management topics at industry events. He is currently a technical-sales representative for Union Ink Co., Inc.

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Screenprinting Magazine.

Most Popular

-

Case Studies2 months ago

Case Studies2 months agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns3 weeks ago

Columns3 weeks ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note3 weeks ago

Editor's Note3 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Marshall Atkinson3 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson3 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago

Thomas Trimingham2 months ago“Magic” Marketing for Screen Printing Shops

-

Case Studies3 weeks ago

Case Studies3 weeks agoScreen Printing for Texture and Depth