Digital Printing

Published

23 years agoon

All of us are familiar with the pitfalls and challenges we face in dealing with digital artwork and the countless electronic configurations in which it may be presented to us. Yet, just as we have with the screen-printing process, we somehow find a way to make digital designs work. Granted, the results are often not exactly what we thought they would be, but we plod along, making gradual improvements in our prepress procedures and learning from each new challenge.

All of us are familiar with the pitfalls and challenges we face in dealing with digital artwork and the countless electronic configurations in which it may be presented to us. Yet, just as we have with the screen-printing process, we somehow find a way to make digital designs work. Granted, the results are often not exactly what we thought they would be, but we plod along, making gradual improvements in our prepress procedures and learning from each new challenge.

We know that there has to be a better way in the long run if we are to remain competitive. But with designers facing an ever-increasing list of end uses for their images and a growing collection of tools for creating them, we can only expect the obstacles facing our prepress technicians to become greater. To better understand the challenges that lie ahead, let’s start by looking at the evolution of digital artwork.

The rise of digital art

The evolution of digital art, as we know it, has followed a relatively predictable course. Conventional layout and design migrated to the electronic desktop in the early 1990s. Screen printers watched to see if the sky would fall as they hurriedly invested in new methods, technology, and training. Everything about this digital art was almost, sorta’ there. No one really knew what was going on, and there was plenty of blame to go around whenever a job went bad or did not live up to expectations.

Through all of this, our clients participated in varying ways. Initially they had their art prepared through ad agencies or traditional graphic designers. We printers were always the ones who had to figure out what the agency or designer missed–the same as we did when art preparation was all analog. But gradually a transition began to take place.

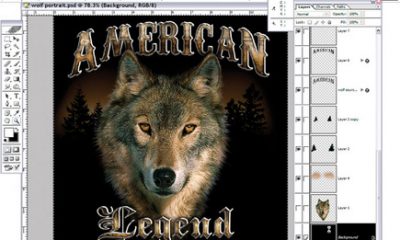

Two things happened simultaneously. The first was that the cost of desktop publishing dropped dramatically. Million-dollar retouching systems were replaced with $15,000 Macintosh workstations. Coupled with this was the introduction of Adobe Photoshop. That event single-handedly changed the way commercial art is created.

Now our clients could do it all in house. Granted, the quality of customer-created artwork was not nearly as high as what we were used to seeing from professional designers. But the cost difference–and the convenience and control of keeping the design process in house–was so great that our customers made the decision for us.

This trend has continued for the last five years. Desktop equipment is now ridiculously cheap, and virtually every printer and print customer has immediate access to it. Whether our computers are Mac or PC really does not make a difference; both platforms offer tremendous computing power and value. Photoshop has become the "killer app" for image preparation and manipulation with roughly a 90% marketshare. No one who prepares art for commercial reproduction is without it.

The second simultaneous occurrence was the emergence of digital design for the Internet. The debate rages on about the future of graphic communications. Will it be all electronic? Will print survive? Nobody knows the answers to these questions. But my gut feeling from watching this debate for the last decade is that print is going to be with us for a very long time. It is just another medium, as is the Internet.

The one thing I know for sure is that there are no longer any clear dividing lines between disciplines. Where does design end and computer programming begin? How does design interface with database architecture? What exactly is graphic communications?

The era of repurposing

Today, graphic communications means that any image is likely to be used in many different ways. In the recent past, digital images were created with specific purposes in mind. They were saved in vector or raster format, depending on the final application, and they were specified for the Web or for print. But designers found themselves preparing the same image in many different ways for each of these different uses. This phenomenon of "repurposing" images for multiple uses is one of the greatest challenges we printers face today.

The concept of repurposing poses some very interesting questions for us. The most obvious is whether we will receive the artwork (or in today’s jargon, the "digital asset") in a form that is acceptable for our particular use. Will the resolution be high enough? Will it be in RGB or some form of CMYK? Will we be able to modify or adapt the image successfully? How much data will be lost in translating the image to a format we can use?

These are exactly the kinds of questions we must answer as we adapt to a digital workflow. Each and every graphic medium has its own workflow, and screen printers, offset printers, large-format print providers, web designers, and other graphic-arts businesses all want to make sure that their unique needs are being met adequately by designers.

However, we cannot rely on designers for the solution. Few are knowledgeable about the techniques and technology behind multiple printing processes or electronic media. If designers know anything about printing, lithography is the process that they’re most likely to be familiar with. So, as usual, the responsibility falls on us to adapt the artwork we receive so that it works in screen printing.

The burden on screen printers will only get worse. As technology continues to race ahead, it is becoming physically impossible to train designers to be knowledgeable in all of the digital design tools they might need and also be competent about print reproduction. I doubt whether it will even be possible for the designers to keep up with the Internet side of things.

As we move to a more and more developed e-commerce side of the business Internet, the pressure on designers will increase. It is not enough that they know Photoshop, Illustrator, Quark, Dreamweaver, and the host of other programs used to create their graphics. They must also have a working knowledge of HTML, XML, DHTML, Java, CGI, Perl, and numerous other scripting and programming languages. These technical requirements are usually not the strength of creative types–they do not like being bogged down in analytical details. Consequently, the designers of tomorrow are on a collision course with the end uses for the graphics they create. Whether the job involves print or the Internet, implementing digital graphics will be where the problems occur.

Enter the digital-asset manager

To address this obvious challenge, a new type of entity is emerging. You can call it a digital-asset manager. Many different incarnations already exist, but despite the need for their unique services, they have not yet been fully embraced. A digital-asset manager could be a company, Website, or computer application. It really does not matter. The objective is that the asset manager controls and tracks all of the details that typically seem to be lost, regardless of what end uses the digital image is destined for.

Here is how an Internet version might work. A large customer (say Coca-Cola), has thousands of digital graphic assets. They are used on screen-printed T-shirts and posters, offset-printed magazine ads, inkjet-printed vehicle graphics, Websites, and so forth. Each time an asset is used, it must be repurposed for that application.

The client (Coke) contracts with the asset manager, who catalogs all of the assets into a searchable visual database. Keywords are embedded to make the search process easier. For each asset, technical specifications are provided to address all of the various uses of the image.

The image becomes part of a huge data warehouse. The managing entity then acts as a facilitator, providing the image and application-specific instructions for those who need access to the graphic. In a way, the asset managers are high-tech middlemen who facilitate easy transfer and use of the client’s digital asset for anyone who needs it and has permission to use it.

The asset manager handles permission for use in a secure way, allowing data exchanges only through a "secure area" of the Website. This means that everything entering and leaving the secure area is encrypted and protected against unauthorized use. It is all but impossible to break the digital code, and the digital certificates or digital signatures the encoding provides are assurances that you are who you say you are and that you have permission to use the graphics.

The companies that are putting together such asset-management services see a very large opportunity to facilitate business. They are often called collaborative sites, and their value to the client is in expediting the process of getting something printed. It does not matter what imaging process is employed–they will manage the preparation of the image and production of the job. To do so, they will form partnerships with various printers in specific regions and product areas.

Many of the key people behind these collaborative sites have managed print projects for years. They may have been print brokers, traffic managers, print buyers, or some other type of print estimator or expeditor. By drawing on the expertise of individuals that are versed in specific processes, markets, or substrates, the collaborative site can make some money while smoothly shepherding the job along.

Watch and wait

If all this sounds interesting, but you are not quite sure how it is all going to work, don’t feel alone. The collaborative portals or Websites have been in development for almost two years, and only a few of the several dozen that have been announced are actually up and running. To date, the results from these functioning collaborators are mixed. Some companies love the idea of digital-asset management and have embraced it completely, while others have not.

The majority of these Internet-based businesses are still unprofitable, and as we have seen since the second half of last year, unprofitable Internet companies have not fared well. Once their cash is gone, so are they. Virtually all of the companies I studied had raised millions in venture capital and were counting on more funding rounds before it was all over.late spring 2001, we will have a better idea of who the survivors will be. In the meantime, have a seat on the sidelines until the dust settles. The important thing to remember is, there is business to be had when the winners emerge.

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Screenprinting Magazine.

Most Popular

-

Case Studies2 months ago

Case Studies2 months agoHigh-Density Inks Help Specialty Printing Take Center Stage

-

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months ago

Art, Ad, or Alchemy2 months agoF&I Printing Is Everywhere!

-

Andy MacDougall2 months ago

Andy MacDougall2 months agoFunctional and Industrial Printing is EVERYWHERE!

-

Columns1 month ago

Columns1 month ago8 Marketing Mistakes Not to Make When Promoting Your Screen Printing Services Online

-

Editor's Note4 weeks ago

Editor's Note4 weeks agoLivin’ the High Life

-

Marshall Atkinson4 weeks ago

Marshall Atkinson4 weeks agoHow to Create a Winning Culture in Your Screen-Printing Business

-

Case Studies1 month ago

Case Studies1 month agoScreen Printing for Texture and Depth

-

News & Trends2 months ago

News & Trends2 months agoWhat Are ZALPHAS and How Can You Serve Them in Your Print Business?